As Massachusetts reels from losing millions of federal research dollars, it’s easy for us as research scientists to lose hope. It’s also easy to believe that with dwindling resources, we live in an even more dog-eat-dog world in which we must fight for the remaining grants and awards. But despite the challenges we are facing, we can choose to see this as a season of possibility—full of potential new ways to carry out our work that involve more collaboration, more partnership, and less competition.

As Massachusetts reels from losing millions of federal research dollars, it’s easy for us as research scientists to lose hope. It’s also easy to believe that with dwindling resources, we live in an even more dog-eat-dog world in which we must fight for the remaining grants and awards. But despite the challenges we are facing, we can choose to see this as a season of possibility—full of potential new ways to carry out our work that involve more collaboration, more partnership, and less competition.Of course, researchers have long worked with colleagues and shared their findings with those in their field. But this particular moment—in which scientific research is under attack from the Trump administration—calls for much deeper collaboration: researchers must come together within, across, and even beyond our fields to determine what the real research questions are, identify whose skills are best suited to answer these questions, and design projects that produce data and information that our communities and policymakers can act upon.

We are ready to meet the moment: We are a group of early childhood policy researchers who are currently developing a statewide early childhood policy research collaborative in Massachusetts. We believe in a broad definition of “researcher”: included in our ranks are traditional academics; research scientists from think tanks; community-based measurement, evaluation, and learning professionals; government analysts; and participatory action practitioners from the field.

We recently held the first Massachusetts Early Childhood Policy Research Summit, at which we, alongside policymakers, advocates, funders, students, and practitioners, committed to working in coordination with each other. Together, we had over 100 participants and filled an entire day with discussion about the role of research, data, design, and collaboration in pushing our field forward. In her opening remarks, Rep. Alice Peisch noted her surprise at just how many researchers of all kinds want to work toward building a more collaborative network across the Commonwealth; those in the room agreed—we even surprised ourselves.

What does a research collaborative mean in practice? It means an annual summit and regular meetings of our leadership team, as well as several working groups focused on specific topics and methods of engaging the field. We decide as a group on our goals, mission, and values, taking into consideration the perspectives of researchers, practitioners, policymakers, and others across the field. We create a website and database of resources to keep our members connected. And, we think collectively about which projects to pursue, consider which of us is best positioned to pursue them, and strategize on how to get it all done and into the hands of those who can take action to support young children, families, and early educators across the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

We are not the first to pursue this model. Similar early childhood policy research collaboratives exist in New York City, Chicago, New Hampshire and several other cities and states. In addition, the National Network of Education Research-Practice Partnerships (NNERPP) is a professional learning community that supports partnerships between researchers and education agencies in order to improve the relationships between research, policy, and practice. These partnerships are considered “a promising strategy for producing more relevant research, improving the use of research evidence in decision making, and engaging both researchers and practitioners to tackle problems of practice.” We agree that this is a promising strategy. It is far more effective for us to approach policymakers as a collaborative of more than 100 members than it is for us to approach them as individual researchers or even as individual institutions.

Does this kind of collaboration sound too good to be true? Certainly, there are challenges to working collaboratively in this way, especially when you’re forming partnerships across research institutions. People have to be willing to move out of their silos and out of the mindset of competition, which most of us have been in our entire careers as we competed against each other for grants, projects, and awards. Another challenge is simply finding the time to collaborate—to meet with each other, to build trusting relationships, and to work through difficult conversations.

But despite these challenges, we all understand that when funding opportunities are limited—and when the problems we aim to address persist—we can’t waste time and money unnecessarily replicating each other’s work or competing for the benefit of our individual institutions. This summer, we expanded our leadership team and supported a working group to keep up the momentum and ensure that collaboration is built into the design of our work together; we were 25 individuals representing 19 colleges and universities, research firms, government agencies, and direct service organizations. We’re excited to continue our work into next year—and to welcome many more researchers, data analysts, and designers of all walks to our 2026 summit.

In order to continue work that can positively impact children, families, and communities in Massachusetts, we must work together. We are ready.

Wendy Wagner Robeson, Ed.D., is a Senior Research Scientist at the Wellesley Centers for Women. Kimberly Lucas, Ph.D., is Professor of the Practice in Public Policy and Economic Justice in the School of Public Policy and Urban Affairs at Northeastern University. And Kyle DeMeo Cook, Ph.D., is Clinical Assistant Professor at Wheelock College of Education and Human Development at Boston University.

The technological world is all around us and developing at a speed that is impossible to keep up with. Adolescents are now more connected to technology than ever before and face both opportunities and obstacles online. Learning to use technology is similar to learning how to drive a car; there are risks involved, and drivers need to learn certain rules and receive gentle guidance before driving on their own. Parents in both scenarios should be in the passenger seat next to their child: setting boundaries, but giving their child the autonomy to eventually thrive on their own. It’s easy to be afraid of the unknown in the digital world, but parental involvement is essential.

The technological world is all around us and developing at a speed that is impossible to keep up with. Adolescents are now more connected to technology than ever before and face both opportunities and obstacles online. Learning to use technology is similar to learning how to drive a car; there are risks involved, and drivers need to learn certain rules and receive gentle guidance before driving on their own. Parents in both scenarios should be in the passenger seat next to their child: setting boundaries, but giving their child the autonomy to eventually thrive on their own. It’s easy to be afraid of the unknown in the digital world, but parental involvement is essential.  As Father’s Day approaches, many of us are thinking about the role that fathers play in our lives—whether they are our own fathers, our spouses, our relatives, our children. I spend more time than the average person thinking about the role that fathers play. Specifically, I study the conversations they have (or in many cases, don’t have) with their teenage children about sex and relationships, and the effects these conversations have on their teens’ health.

As Father’s Day approaches, many of us are thinking about the role that fathers play in our lives—whether they are our own fathers, our spouses, our relatives, our children. I spend more time than the average person thinking about the role that fathers play. Specifically, I study the conversations they have (or in many cases, don’t have) with their teenage children about sex and relationships, and the effects these conversations have on their teens’ health.

What better place to foster a love of reading and engage children in a variety of literacy activities than in out-of-school time (OST) programs? Research shows that OST programs can support the development of and excitement about literacy in a setting where children feel comfortable.

What better place to foster a love of reading and engage children in a variety of literacy activities than in out-of-school time (OST) programs? Research shows that OST programs can support the development of and excitement about literacy in a setting where children feel comfortable. Beginning in the mid-1990s, with my colleague, Benjamin E. Saunders, Ph.D., of the Medical University of South Carolina, and a team of researchers, I conducted an

Beginning in the mid-1990s, with my colleague, Benjamin E. Saunders, Ph.D., of the Medical University of South Carolina, and a team of researchers, I conducted an  Last year, the U.S. Surgeon General

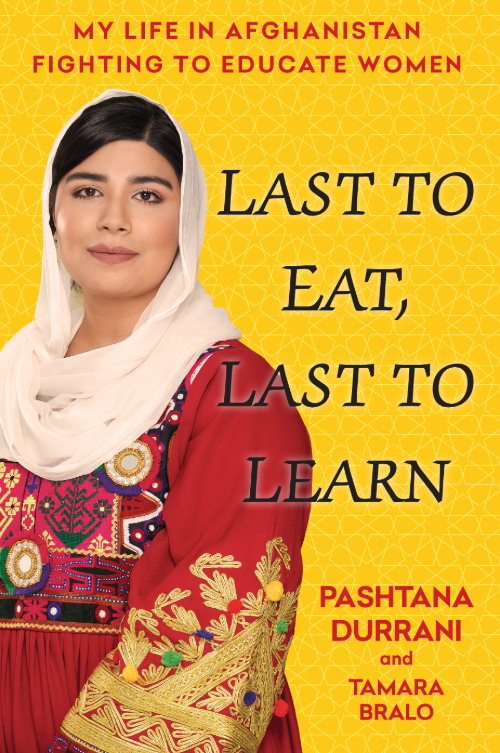

Last year, the U.S. Surgeon General  With a collection of government stamps in hand, I now needed to secure the tribal backing for the project. Government approval merely made my NGO official, but without the tribal endorsement, my effort to educate girls would be just another import with a short shelf life.

With a collection of government stamps in hand, I now needed to secure the tribal backing for the project. Government approval merely made my NGO official, but without the tribal endorsement, my effort to educate girls would be just another import with a short shelf life. Dear Friends of WCW:

Dear Friends of WCW:

Below is an excerpt by Betsy Nordell, Ed.D., a NIOST master observer, from the book

Below is an excerpt by Betsy Nordell, Ed.D., a NIOST master observer, from the book

Nearly

Nearly

, Ph.D., is a research scientist at the Wellesley Centers for Women studying

, Ph.D., is a research scientist at the Wellesley Centers for Women studying

Critical race theory has become the latest front in the culture wars. Depending on what you’ve read or what you’ve heard from politicians, you may be under the impression that critical race theory means talking about racism in any context, or that it means white people are inherently racist.

Critical race theory has become the latest front in the culture wars. Depending on what you’ve read or what you’ve heard from politicians, you may be under the impression that critical race theory means talking about racism in any context, or that it means white people are inherently racist. Senior Research Scientist

Senior Research Scientist  May is Mental Health Awareness Month. This year, it comes at a time when we have an increased focus on mental health due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Media reports have focused on the

May is Mental Health Awareness Month. This year, it comes at a time when we have an increased focus on mental health due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Media reports have focused on the  April is Sexual Assault Awareness Month and Child Abuse Prevention Month. Over the years, our work at WCW has addressed a wide range of critical issues related to these topics. One of the lesser publicly understood issues is the pressing problem of commercial sexual exploitation of children (CSEC) and teens, also known as sex trafficking.

April is Sexual Assault Awareness Month and Child Abuse Prevention Month. Over the years, our work at WCW has addressed a wide range of critical issues related to these topics. One of the lesser publicly understood issues is the pressing problem of commercial sexual exploitation of children (CSEC) and teens, also known as sex trafficking. On March 11, 2021, the House of Representatives passed a bill seeking to “create a special education scheme to support deserving students attending public tertiary institutions across Liberia. The Bill is titled “An Act to Create a Special Education Fund to Support and Sustain the Tuition Free Scheme for the University of Liberia, All Public Universities and Colleges’ Program and the Free WASSCE fess for Ninth and Twelfth Graders in Liberia, or the Weah Education Fund (WEF) for short. The bill when enacted into law, will make all public colleges and universities “tuition-free”. The passage of this bill by the Lower House has been met by mixed reactions across the country: young, old, educated, not educated, stakeholders, parents, teachers among others, have all voiced their opinions about this bill. While some are celebrating this purported huge milestone in the education sector, others are still skeptical that this bill may only increase access but not address the structural challenges within the sector. I join forces with the latter, and in this article, I discuss the quality and access concept in our education sector and why quality is important than access. I recommend urgent action to improve quality for learners in K-12.

On March 11, 2021, the House of Representatives passed a bill seeking to “create a special education scheme to support deserving students attending public tertiary institutions across Liberia. The Bill is titled “An Act to Create a Special Education Fund to Support and Sustain the Tuition Free Scheme for the University of Liberia, All Public Universities and Colleges’ Program and the Free WASSCE fess for Ninth and Twelfth Graders in Liberia, or the Weah Education Fund (WEF) for short. The bill when enacted into law, will make all public colleges and universities “tuition-free”. The passage of this bill by the Lower House has been met by mixed reactions across the country: young, old, educated, not educated, stakeholders, parents, teachers among others, have all voiced their opinions about this bill. While some are celebrating this purported huge milestone in the education sector, others are still skeptical that this bill may only increase access but not address the structural challenges within the sector. I join forces with the latter, and in this article, I discuss the quality and access concept in our education sector and why quality is important than access. I recommend urgent action to improve quality for learners in K-12.

As a new mother, you hold your baby in your arms, wishing for the best of the best for her. You may also be facing difficult career questions upon her arrival: When should you start working again? Should you be a stay-at-home-mom? Should you get a new job with a more flexible schedule? Will you be able to get promoted when you’re back at work? If you have a daughter, will she face the same choices in the future?

As a new mother, you hold your baby in your arms, wishing for the best of the best for her. You may also be facing difficult career questions upon her arrival: When should you start working again? Should you be a stay-at-home-mom? Should you get a new job with a more flexible schedule? Will you be able to get promoted when you’re back at work? If you have a daughter, will she face the same choices in the future?

Sex education in the American public school system varies from state to state and from school district to school district. The lack of standardized sex education makes family education and conversations about sex and relationships all the more important for teenagers and their development. It is often assumed that parents are the default—that they are the only family members responsible for initiating these conversations. In my research conducted with WCW Senior Research Scientist

Sex education in the American public school system varies from state to state and from school district to school district. The lack of standardized sex education makes family education and conversations about sex and relationships all the more important for teenagers and their development. It is often assumed that parents are the default—that they are the only family members responsible for initiating these conversations. In my research conducted with WCW Senior Research Scientist

I spent the past semester working with Professor

I spent the past semester working with Professor