As a new mother, you hold your baby in your arms, wishing for the best of the best for her. You may also be facing difficult career questions upon her arrival: When should you start working again? Should you be a stay-at-home-mom? Should you get a new job with a more flexible schedule? Will you be able to get promoted when you’re back at work? If you have a daughter, will she face the same choices in the future?

As a new mother, you hold your baby in your arms, wishing for the best of the best for her. You may also be facing difficult career questions upon her arrival: When should you start working again? Should you be a stay-at-home-mom? Should you get a new job with a more flexible schedule? Will you be able to get promoted when you’re back at work? If you have a daughter, will she face the same choices in the future?

When it comes to ensuring that women are able to maintain careers while having children, some progress has been made at the national level, including the Equal Pay Act of 1963 that enforces equal pay for equal work and the Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993 that requires covered employers to provide employees with unpaid leave for qualified medical and family reasons. However, these laws are not nearly enough to eradicate gender inequality in the workplace or the gender wage gap.

Today is Equal Pay Day, a symbolic occasion that raises awareness about the wage gap. The date represents how far into the year U.S. women must work to earn what men earned in the previous year. This year, Equal Pay Day is August 3 for black women, September 8 for Native American women, and October 21 for Latina women. While many factors contribute to the gender wage gap, two significant factors are the “sorting problem” — overrepresentation of women in low-wage industries and occupations — and gender roles at home.

Despite the fact that in recent years, the percentage of women 25 and older who have at least a bachelor’s degree is higher than the percentage of men, longstanding gender biases cause women to cluster in certain college majors. Women are still scarce in majors related to science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM), a gateway to high-paying jobs. Thus, they are automatically “sorted” into relatively low-paying industries even before starting their careers.

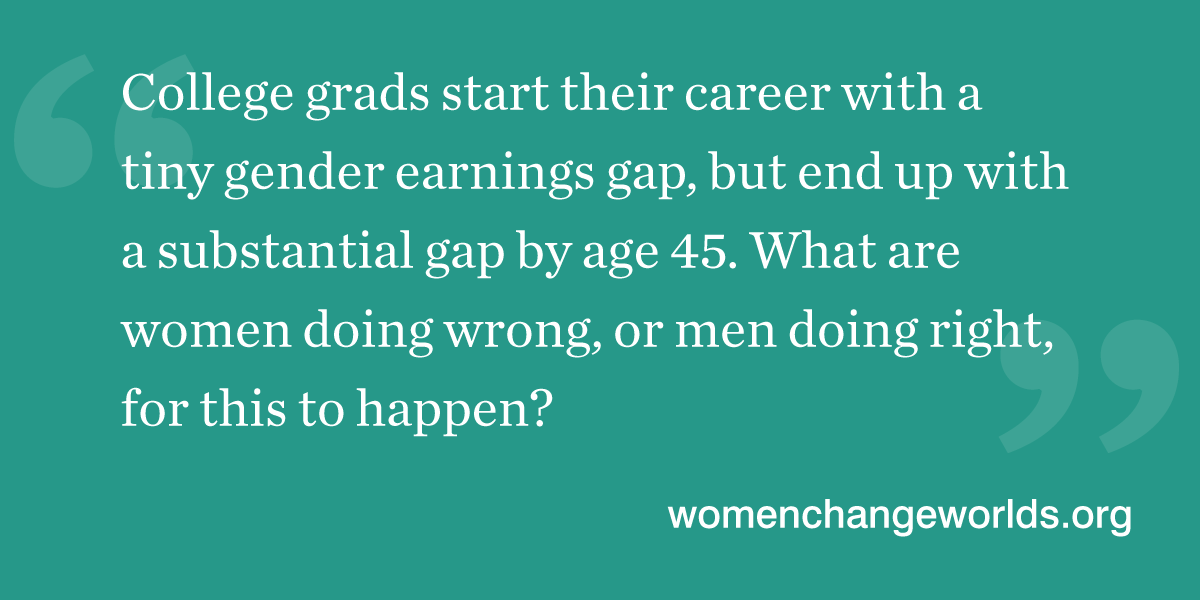

However, even if women follow a career path in a well-paying industry and position, research shows that male and female college grads who start their careers earning similar salaries end up with a substantial gap. Gender roles, especially the fact that women are often primary caregivers for children, are the biggest culprit. Some women choose to be stay-at-home moms, some switch to more flexible or part-time positions, and others just cannot keep up with the demands of their jobs enough to be promoted. Hence, the gap widens.

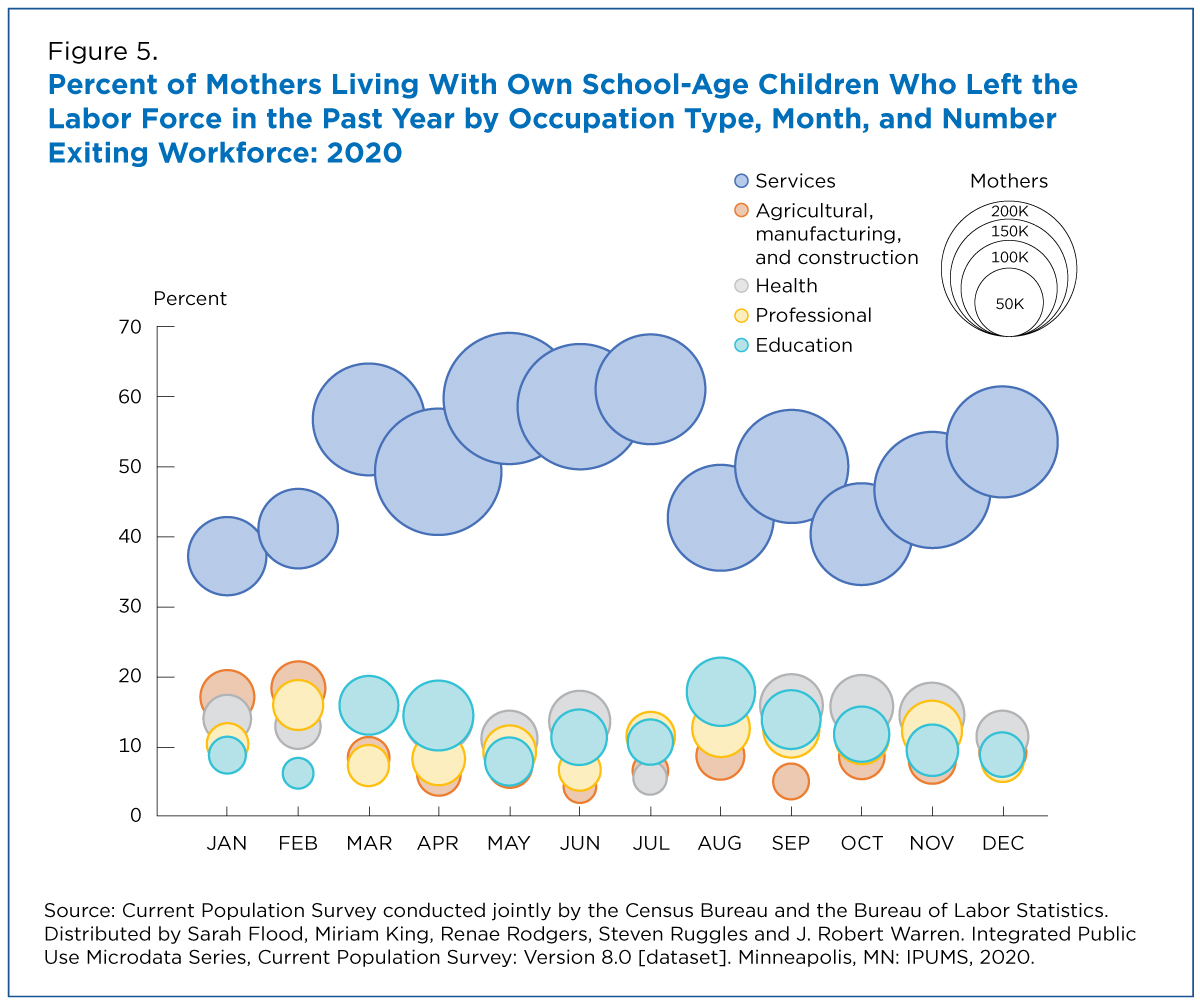

The economic effects of the COVID-19 crisis have brought out the worst of the consequences of the sorting problem and gender roles. First, industries like hospitality and retail, which are dominated by women, have been hit the hardest. Second, mothers have been especially vulnerable due to the lack of childcare and increased home responsibilities such as homeschooling. Now many are calling this crisis a “she-cession,” and the burden is not only financial but also psychological.

These effects could have been less severe if policies were in place to fix systemic gender inequalities. The pandemic has revealed the urgency of implementing actionable and effective policies that will set us on a path toward a gender-equitable recovery as well as a gender-equitable future.

For example, we need policies that promote an education system free of gender bias, in which girls are encouraged to pursue careers in STEM fields. We need to invest in affordable child care and flexible work schedules for all. And we need to design optimum paid parental leave policies that help parents to achieve a more manageable work-family balance and improve the labor market outcomes of women as well as the health and wellbeing of both children and mothers, while incentivizing firms to promote equality in the workplace.

At WCW, my research focuses on understanding the impacts of current paid leave laws in the U.S. Unfortunately, the U.S. is the only developed country with no federal paid family leave. However, there are some states with job-protected paid leave laws and some others with legislation underway. Research to date on the effects of these laws is limited and based mostly on California data since it was the first state to enact such a law, in 2004. Some studies based on California data show that it has a positive impact on employment and wages of new mothers, especially in the short run, while others find contradictory evidence in the long run.

Clearly, we need further research. Our research with the Longitudinal Business Database and the Longitudinal Employer-Household Dynamics database, linked to the 2000 Census and American Community Surveys (2005-2017), is more comprehensive than previous studies and will broaden our knowledge to design better policies as it includes New Jersey and Rhode Island data and looks at employee-employer relationships.

It will take time to change social norms and prejudices, and to eliminate gender discrimination that is engraved in our social fabric. But as we pursue research that shows us which policies can help, we advance gender equality, social justice, and human wellbeing. Equal Pay Day reminds us that we must keep fighting this fight, in order to create a better future for our children.

Deniz Çivril, Ph.D., is a research scientist at the Wellesley Centers for Women at Wellesley College and Special-Sworn-Status researcher at the U.S. Census Bureau. Her research interests center on labor economics, international trade, and corporate finance. Her current projects at WCW focus on women in the workplace.

A woman graduates from college and starts her first job, earning about the same as the male colleague who sits next to her. She gets promoted a few times, her salary increases, and in her late 20s, she gets married. Her husband gets a job offer in a new city, they move, and she takes a slightly lower-paying job. In her early 30s, she has a baby, and then another baby in her mid-30s. She decides to cut back her hours (and thus her pay) in order to spend more time with her children.

A woman graduates from college and starts her first job, earning about the same as the male colleague who sits next to her. She gets promoted a few times, her salary increases, and in her late 20s, she gets married. Her husband gets a job offer in a new city, they move, and she takes a slightly lower-paying job. In her early 30s, she has a baby, and then another baby in her mid-30s. She decides to cut back her hours (and thus her pay) in order to spend more time with her children.  We all have heard it, women earn about 20 percent less than men. But when, how, and why does the gap emerge? Everyone has an opinion on it, and these opinions range widely – which leads to many

We all have heard it, women earn about 20 percent less than men. But when, how, and why does the gap emerge? Everyone has an opinion on it, and these opinions range widely – which leads to many  Another expensive “choice” women make is motherhood. Women are more likely to

Another expensive “choice” women make is motherhood. Women are more likely to