This blog was originally published on the HowlRound website on December 1, 2015, and is re-posted with permission.

This week on HowlRound, we continue the conversation on gender parity, which has been gaining momentum this year through studies, articles, forums, one-on-one discussions, and seasons and festivals focused on women. As Co-President of the Women in the Arts & Media Coalition and VP of Programming for the League of Professional Theatre Women, I have the pleasure of working with, coordinating, contributing to, and raising awareness about many of these local, national, and international efforts. This series explores what needs to happen right now—in this precipitous moment—in order to profoundly, permanently expand the theatrical community's views and visions of women, both onstage and in every aspect of production.

When people unfamiliar with the world of theatre learn that our current research is on why there are too few women leading major U.S. theatres, their first comment is, “But it’s better than it used to be, right?” We say, “No, the situation hasn’t changed for decades.” They respond with, “I don’t understand, look at Lynne Meadow, look at Diane Paulus.” We say, “Yes, there are a few illustrious examples.” Unfortunately, comparisons with the “bad-old-days” and mention of token successes also showed up frequently in our interviews with 100 theatre professionals. Furthermore, they added, “Racial minorities have it worse, that’s where we should focus our attention to diversify leadership.”

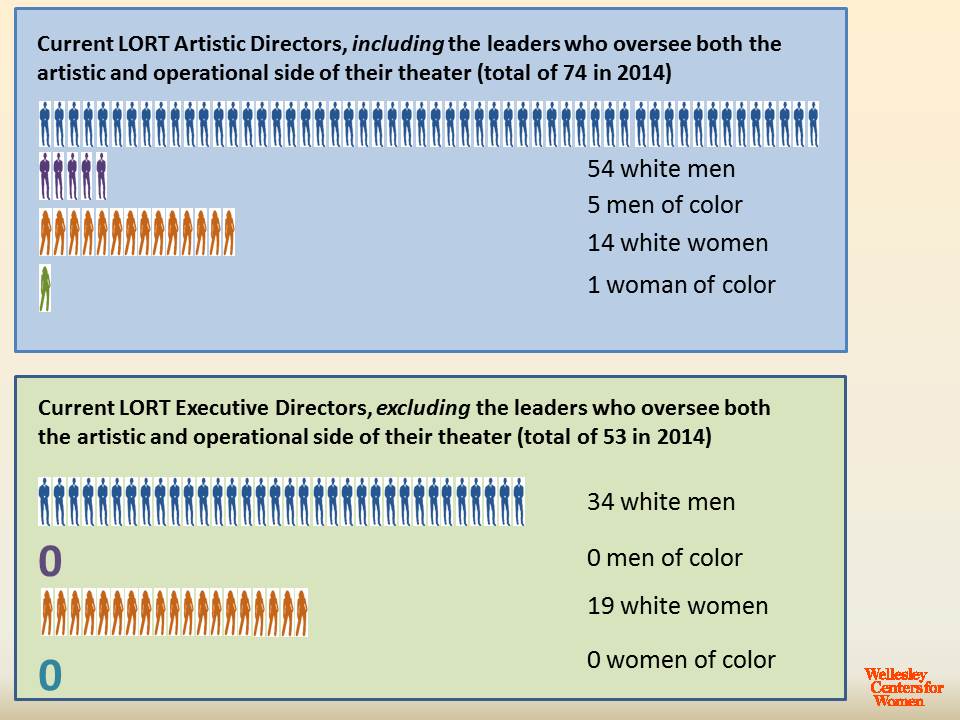

In 2013, the leadership of the American Conservatory Theater in San Francisco approached us at the Wellesley Centers for Women to be their research partner for studying gender equity in LORT leadership. There were only fifteen women who served as artistic directors, or held the combined Artistic Director/CEO position in the seventy-four LORT theatres at the time. The situation on the executive/managerial side of the theatres was better, but not much: there were nineteen female leaders. There was only one female artistic director of color. For men of color, leadership representation was also bleak: there were five leaders on the artistic side, and like women of color, none were top executive/managerial leaders. Our research, which is supported by the Virginia B. Toulmin Foundation and individual donors, suggests that many issues associated with the scarcity of women in top leadership are also true of people of color. Pointing to the scarcity of people of color to avoid paying attention to women is an excuse. There needs to be action on both fronts, paying particular attention to the virtual absence of women of color in theatre leadership.

Our research strategy aimed at better understanding the career paths of those in current leadership in order to make recommendations for aspiring future leaders in the pipeline and examining the search process to make recommendations to hiring committees. We had two informant pools: our primary charge was within LORT, so we focused on current leaders and their immediate reports within the League through interviews and resume analyses. Because candidates for leadership can come from both inside and outside of LORT, we also gathered anonymous survey data from stage director members of SDC and operational managers in TCG theatre members with a budget of over $1 million.

Demographics (of gender and race) in LORT Leadership. Photo courtesy of Wellesley Centers for Women.

First, we studied the pipeline. The career path toward an artistic director (AD) position is strongly defined by “whom you play in the sandbox with,” in the words of one of our interviewees. The skills of directing and producing can best be honed by getting invitations from multiple theatres to bring a variety of plays to the stage. But skills are not enough. To have a shot at top leadership, directors and producers need to build relationships with people who can speak to their strengths and can vet their reputation. In our survey with almost 1,000 stage directors, women highlighted two barriers toward succeeding in their quest to become the artistic leader of a theatre: a lack of opportunities to direct widely to strengthen their portfolio, and not having someone speaking to their strengths. Stage directors of color (both women and men) added to these two barriers faced by white women that they also confronted being pigeonholed into directing plays by playwrights of color.

So, yes, there is a pipeline issue facing women and people of color in their preparation for artistic leadership. How do we strengthen the pipeline?

1. Make conscious, planned, and thoughtful decisions to include women and people of color as directors and producers in programming each and every season to provide them with frequent, varied opportunities.

2. Travel and relocation are real obstacles for both men and women with families, but the preconceived notion that “they won’t want to come and do this” is a stronger barrier for women. If these issues do present a challenge, be willing to accommodate the director’s needs.

3. ADs should invite directors of color to direct the classics as well as new plays to support their portfolio growth.

A word of caution: To conclude that the main problem is a pipeline issue and over time more women and people of color will become viable candidates is an incomplete diagnosis of the problem, and an excuse. It dismisses the large numbers of producers and directors who are well prepared and eager to take on artistic director positions. In addition to the pipeline, there is just as profound a glass ceiling that can be broken with a change in mindset among those who make hiring decisions. Here are some action points for hiring committees about selecting ADs:

A word of caution: To conclude that the main problem is a pipeline issue and over time more women and people of color will become viable candidates is an incomplete diagnosis of the problem, and an excuse. It dismisses the large numbers of producers and directors who are well prepared and eager to take on artistic director positions. In addition to the pipeline, there is just as profound a glass ceiling that can be broken with a change in mindset among those who make hiring decisions. Here are some action points for hiring committees about selecting ADs:

1. Don’t overlook the sizable number of women directors and producers, including women of color, who have founded theatre companies, and have developed expertise in all aspects of artistic leadership. These women constitute a viable, immediately available pool of candidates, but are being overlooked in searches and are waiting just below the glass ceiling. Curiously, we found previous AD experience to be prevalent in the background of male, but not female artistic directors within LORT.

2. Be willing to go beyond your comfort zone and the current model of the male leader to trust and select women (and people of color) candidates. A fair number of female LORT ADs had worked in a LORT theatre prior to their AD appointment. These women were known and trusted, hence were promoted. There are many other talented women (directors and creative producers) who have the necessary skills without having worked in LORT. They need to be pulled into the search process.

3. Learn how to and then actively support any candidate’s success once on the job and continue to mentor them. One AD of color we interviewed points out that gender should hardly matter in choosing a candidate: “... nobody is prepared for one of these jobs when they come into it.” All new hires, male or female, people of color or white, will need support from their Board to succeed.

4. Move toward developing metrics for vetting leadership candidates to create greater transparency in the selection process and provide guidance to people in the pipeline. These metrics can also be used to evaluate the wisdom of the board’s selection and the performance of the candidate chosen.

Women have fared slightly better on the operational side of LORT theatres, outnumbering men in all departments, except executive/managerial directors (ED). So there is no pipeline problem for ED appointments; the absence of women at the top is clearly a glass ceiling issue. All it will take is for search committees to have the resolve to move beyond the model of having a man as the operational leader. But the lack of a pipeline issue for women aspiring to become EDs is true only for white women. Women of color are far fewer on the operational side and there is no woman of color who is the ED of a LORT theatre. For women of color, there is both a pipeline and a glass ceiling issue preventing their presence at the top. In our surveys, both women of color and white women’s comfort and expertise with fundraising come through as their strongest assets, and should be reasons for Board selection committees to seek them out. Indeed, a background in development is well represented among white female EDs. However, women managers reported that they are just as comfortable with budgeting, contracts, or real estate law. Ignoring these talents by placing the majority of women in development is limiting the pipeline and solidifying stereotypes that general management and finance are male domains.

Breaking the glass ceiling by creating more opportunities for women and people of color among current leadership in LORT now, without further delay, will serve as a route to simultaneously grow the pipeline reaching all the way down to high school teens who will learn to see the theatre as a possible and viable option among their career choices.

Sumru Erkut, Ph.D. and Ineke Ceder are members of the research team at the Wellesley Centers for Women, working on the Women's Leadership in Residential Theaters project.

Beatrice’s education. As a result, Beatrice made it all the way to

Beatrice’s education. As a result, Beatrice made it all the way to  Recently, Beatrice updated us about her activities, which have grown to support the communities where she works in even broader ways. In addition to a library/community center in Amor Village, which was her project under IREX, she has now started a school complex in Tororo village that already includes a primary school and will grow to include a nursery school, a secondary school, and a vocational education center. Twenty-seven of the mentees who started with PCEF/RGCM at the beginning of secondary school are now pursuing university education. About half of them are studying to become teachers, but the others are pursing fields as diverse as accounting and finance, adult education, economics, motor mechanics, clinical medicine, nursing, human resource management, and wildlife management. Finally, Beatrice is mobilizing donors to purchase solar panels for the families in her network so that they can stop using kerosene lamps. She just thinks of everything!

Recently, Beatrice updated us about her activities, which have grown to support the communities where she works in even broader ways. In addition to a library/community center in Amor Village, which was her project under IREX, she has now started a school complex in Tororo village that already includes a primary school and will grow to include a nursery school, a secondary school, and a vocational education center. Twenty-seven of the mentees who started with PCEF/RGCM at the beginning of secondary school are now pursuing university education. About half of them are studying to become teachers, but the others are pursing fields as diverse as accounting and finance, adult education, economics, motor mechanics, clinical medicine, nursing, human resource management, and wildlife management. Finally, Beatrice is mobilizing donors to purchase solar panels for the families in her network so that they can stop using kerosene lamps. She just thinks of everything!

responding to and addressing such backlogs, including policies and protocols for notifying and involving victims. States and local jurisdictions have also been responding by implementing backlog reduction legislation or initiatives.

responding to and addressing such backlogs, including policies and protocols for notifying and involving victims. States and local jurisdictions have also been responding by implementing backlog reduction legislation or initiatives. director of the Women’s Law Project, who was honored by the

director of the Women’s Law Project, who was honored by the

Thirty-six years later, the social status of LGBT people has changed enormously. Few LGBT people in Montana, say, would worry that a march in Washington, DC, would cause them to be set upon by an angry mob. In liberal Massachusetts, my employer, my neighbors, and my doctor all know I’m a lesbian. I’ve been married to my partner of 27 years since 2003—and my entire family came to our wedding. Since the Supreme Court’s Obergefell decision in June, my marriage is recognized by the federal government as well as that of my state. I can watch many television shows and movies in which LGBT characters make it through the entire plot without killing themselves. I can kiss my wife goodbye on the front steps when I leave for work in the morning without worrying (too much) that we’ll be beaten or shot.

Thirty-six years later, the social status of LGBT people has changed enormously. Few LGBT people in Montana, say, would worry that a march in Washington, DC, would cause them to be set upon by an angry mob. In liberal Massachusetts, my employer, my neighbors, and my doctor all know I’m a lesbian. I’ve been married to my partner of 27 years since 2003—and my entire family came to our wedding. Since the Supreme Court’s Obergefell decision in June, my marriage is recognized by the federal government as well as that of my state. I can watch many television shows and movies in which LGBT characters make it through the entire plot without killing themselves. I can kiss my wife goodbye on the front steps when I leave for work in the morning without worrying (too much) that we’ll be beaten or shot. Still, as

Still, as  Everyone Needs to STOP the Pain!

Everyone Needs to STOP the Pain! The obvious forms of social pain are glaringly obvious, often flagrant and extreme. Black men and women being stopped by police, detained or harassed, and imprisoned at sweepingly disproportionate rates compared to White people; too often resulting in violence and even murder.

The obvious forms of social pain are glaringly obvious, often flagrant and extreme. Black men and women being stopped by police, detained or harassed, and imprisoned at sweepingly disproportionate rates compared to White people; too often resulting in violence and even murder.

Over the summer, Alan visited us here at the Wellesley Centers for Women, and here’s what he had to say about Maggie>>

Over the summer, Alan visited us here at the Wellesley Centers for Women, and here’s what he had to say about Maggie>>

The three-day conference was full of conversations and speeches by professors, politicians, lawyers, and students from around the world and it helped further shape my ideas about peace and how, instead of been skeptical, I can contribute to achieving world peace. It wasn’t merely these conversations or speeches that shaped my thinking, but mostly by being a part this global community I had the opportunity to use my voice--and the voices of other participants--to rally behind a common good. The conference exposed me to a lot of factors undermining peace around the world as well as possible solutions to tackle them. It brought me face to face with other young people from around the world who had similar experiences as mine but who had examples of proven and possible solutions for peacebuilding. One of those participants was a Canadian law student, originally from Rwanda, who became an immigrant at a tender age because of the genocide in her country. She stressed her idea that peace is possible but only if we focus our efforts on changing international humanitarian laws.

The three-day conference was full of conversations and speeches by professors, politicians, lawyers, and students from around the world and it helped further shape my ideas about peace and how, instead of been skeptical, I can contribute to achieving world peace. It wasn’t merely these conversations or speeches that shaped my thinking, but mostly by being a part this global community I had the opportunity to use my voice--and the voices of other participants--to rally behind a common good. The conference exposed me to a lot of factors undermining peace around the world as well as possible solutions to tackle them. It brought me face to face with other young people from around the world who had similar experiences as mine but who had examples of proven and possible solutions for peacebuilding. One of those participants was a Canadian law student, originally from Rwanda, who became an immigrant at a tender age because of the genocide in her country. She stressed her idea that peace is possible but only if we focus our efforts on changing international humanitarian laws.

services to women and girls who need them. What our clinic staff has seen firsthand is that blocking access to abortion and comprehensive reproductive health care doesn’t stop them from being needed, or even stop them from happening — it just keeps them from being safe. Due in large part to extensive abortion bans throughout the region, 95% of abortions in Latin America are performed in unsafe conditions that threaten the health and lives of women.

services to women and girls who need them. What our clinic staff has seen firsthand is that blocking access to abortion and comprehensive reproductive health care doesn’t stop them from being needed, or even stop them from happening — it just keeps them from being safe. Due in large part to extensive abortion bans throughout the region, 95% of abortions in Latin America are performed in unsafe conditions that threaten the health and lives of women.

Although these are all big questions, I have at least learned a few things over the years through my

Although these are all big questions, I have at least learned a few things over the years through my  Lisa Fortuna

Lisa Fortuna

My academic and teaching interests lie at the intersection of culture, computation, community, and cognition--I like to think about how technology can support learning in community and public settings. In my

My academic and teaching interests lie at the intersection of culture, computation, community, and cognition--I like to think about how technology can support learning in community and public settings. In my  Robbin Chapman

Robbin Chapman

Service occupations, such as maids and housekeeping cleaners, personal care aides and child care workers, are the lowest paid of all broad occupational categories. This disproportionately affects the earnings of

Service occupations, such as maids and housekeeping cleaners, personal care aides and child care workers, are the lowest paid of all broad occupational categories. This disproportionately affects the earnings of

Dr. Hardisty had served on the Board of Directors of the Highlander Center for Research and Education, the Ms. Foundation, the Center for Community Change, and the Center for Women Policy Studies, among others. Her book, Mobilizing Resentment: Conservative Resurgence from the John Birch Society to the Promise Keepers, was first published by Beacon Press in 1999. Some of her WCW-related

Dr. Hardisty had served on the Board of Directors of the Highlander Center for Research and Education, the Ms. Foundation, the Center for Community Change, and the Center for Women Policy Studies, among others. Her book, Mobilizing Resentment: Conservative Resurgence from the John Birch Society to the Promise Keepers, was first published by Beacon Press in 1999. Some of her WCW-related  In the mid-1970s, Stanford-based psychologist

In the mid-1970s, Stanford-based psychologist

Championship, was confused when he arrived on campus. His

Championship, was confused when he arrived on campus. His

ck History Month, which began as Negro History Week in 1926. He was an erudite and meticulous scholar who obtained his B.Litt. from Berea College, his M.A. from the University of Chicago, and his doctorate from Harvard University at a time when the pursuit of higher education was extremely fraught for African Americans. Because he made it his mission to collect, compile, and distribute historical data about Black people in America, I like to call him “the original #BlackLivesMatter guy.” His self-declared dual mission was to make sure the African-Americans knew their history and to insure the place of Black history in mainstream U.S. history. This was long before Black history was considered relevant, even thinkable, by most white scholars and the white academy. In fact, he writes in the preface of The Negro in Our History that he penned the book for schoolteachers so that Black history could be taught in schools—and this, just in time for the opening of Washington High School.

ck History Month, which began as Negro History Week in 1926. He was an erudite and meticulous scholar who obtained his B.Litt. from Berea College, his M.A. from the University of Chicago, and his doctorate from Harvard University at a time when the pursuit of higher education was extremely fraught for African Americans. Because he made it his mission to collect, compile, and distribute historical data about Black people in America, I like to call him “the original #BlackLivesMatter guy.” His self-declared dual mission was to make sure the African-Americans knew their history and to insure the place of Black history in mainstream U.S. history. This was long before Black history was considered relevant, even thinkable, by most white scholars and the white academy. In fact, he writes in the preface of The Negro in Our History that he penned the book for schoolteachers so that Black history could be taught in schools—and this, just in time for the opening of Washington High School. women. It enlivens my curiosity to imagine my grandmother Jannie as a young woman learning in school about her own history from Carter G. Woodson’s text, which, at that time was still relatively new, alongside anything else she might have been learning. It saddens me to reflect on the fact that my own post-desegregation high school education, AP History and all, offered no such in-depth overview of Black history, African American or African.

women. It enlivens my curiosity to imagine my grandmother Jannie as a young woman learning in school about her own history from Carter G. Woodson’s text, which, at that time was still relatively new, alongside anything else she might have been learning. It saddens me to reflect on the fact that my own post-desegregation high school education, AP History and all, offered no such in-depth overview of Black history, African American or African. After finishing high school, my grandmother Jannie, like many of her generation, worked as a domestic for many years. However, after spending time working in the home of a doctor, she was encouraged and went on to become a licensed practical nurse (LPN), which took two more years of night school. From that point until her death, she worked as a private nurse to aging wealthy Atlantans. This enabled her to make a good, albeit humble, livelihood for herself and her two daughters, along with my great grandmother Laura, who lived with her and served as her primary source of childcare, particularly after her brief marriage to my grandfather, an older man who she found to be overbearing, ended. With this livelihood, she was able to put both her daughters through Spelman College, the nation’s leading African American women’s college, then and now. It stands as a point of pride to our whole family that, although she was unable to attend due to family responsibilities, Jannie herself was also at one time admitted to

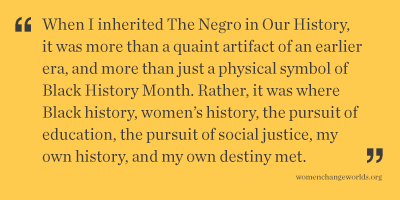

After finishing high school, my grandmother Jannie, like many of her generation, worked as a domestic for many years. However, after spending time working in the home of a doctor, she was encouraged and went on to become a licensed practical nurse (LPN), which took two more years of night school. From that point until her death, she worked as a private nurse to aging wealthy Atlantans. This enabled her to make a good, albeit humble, livelihood for herself and her two daughters, along with my great grandmother Laura, who lived with her and served as her primary source of childcare, particularly after her brief marriage to my grandfather, an older man who she found to be overbearing, ended. With this livelihood, she was able to put both her daughters through Spelman College, the nation’s leading African American women’s college, then and now. It stands as a point of pride to our whole family that, although she was unable to attend due to family responsibilities, Jannie herself was also at one time admitted to  ge. Sadly, she didn’t live to see me attain my Ph.D., but, when she passed away, I was already pursuing my Masters degree, and, like her, I was also mother to a second child. Thus, when I inherited The Negro in Our History, it was more than a quaint artifact of an earlier era, and more than just a physical symbol of Black History Month. Rather, it was where Black history, women’s history, the pursuit of education, the pursuit of social justice, my own history, and my own destiny met.

ge. Sadly, she didn’t live to see me attain my Ph.D., but, when she passed away, I was already pursuing my Masters degree, and, like her, I was also mother to a second child. Thus, when I inherited The Negro in Our History, it was more than a quaint artifact of an earlier era, and more than just a physical symbol of Black History Month. Rather, it was where Black history, women’s history, the pursuit of education, the pursuit of social justice, my own history, and my own destiny met.

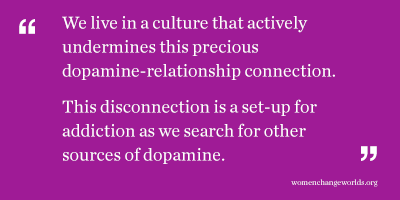

So dopamine itself is not the problem, nor is the dopamine reward system. Dopamine is simply the carrot on a stick designed to give a reward to life-sustaining activities like eating healthy food, having sex, drinking water, and being held in nurturing relationships so that you would keep doing these healthy things over and over again. The problem is how we stimulate the dopamine pathway. In an ideal world—one that understands the centrality of healthy relationship to health and wellness—the dopamine reward system stays connected to human connection as the primary source of stimulation. Unfortunately, we do not live in this ideal world. We live in a culture that actively undermines this precious dopamine-relationship connection. We raise children to stand on their own two feet while the separate self is an American icon of maturity. It is making us sick.

So dopamine itself is not the problem, nor is the dopamine reward system. Dopamine is simply the carrot on a stick designed to give a reward to life-sustaining activities like eating healthy food, having sex, drinking water, and being held in nurturing relationships so that you would keep doing these healthy things over and over again. The problem is how we stimulate the dopamine pathway. In an ideal world—one that understands the centrality of healthy relationship to health and wellness—the dopamine reward system stays connected to human connection as the primary source of stimulation. Unfortunately, we do not live in this ideal world. We live in a culture that actively undermines this precious dopamine-relationship connection. We raise children to stand on their own two feet while the separate self is an American icon of maturity. It is making us sick.

Deep in my brain, the area in the prefrontal cortex that plans and executes the physical movement of walking out the door is being stimulated. Though I am not moving, the same nerve cells are firing. When you touch the door and pull your hand away quickly and shake it a little I “know” that the door was quite hot from the pounding sunshine on the glass. My somatosensory cortex that creates sensations fires and my hand feels a low-grade sense of heat and smoothness from the window window. That is added to the immediate mix of how I am reading your experience. And finally, you walk through the door and a large smile crosses your face as you fall into the arms of a loved one. In my brain and body the nerve signal has now traveled through the insula into my “feeling centers” in my body and I feel a similar joy and lightness. I “know” you are with someone you love. All of this has happened in the blink of an eye and without you sharing any of your experience with me. My brain and body uses itself as a template to have a shared experience with you and the closer our life experiences internally have been, the more resonant we feel.

Deep in my brain, the area in the prefrontal cortex that plans and executes the physical movement of walking out the door is being stimulated. Though I am not moving, the same nerve cells are firing. When you touch the door and pull your hand away quickly and shake it a little I “know” that the door was quite hot from the pounding sunshine on the glass. My somatosensory cortex that creates sensations fires and my hand feels a low-grade sense of heat and smoothness from the window window. That is added to the immediate mix of how I am reading your experience. And finally, you walk through the door and a large smile crosses your face as you fall into the arms of a loved one. In my brain and body the nerve signal has now traveled through the insula into my “feeling centers” in my body and I feel a similar joy and lightness. I “know” you are with someone you love. All of this has happened in the blink of an eye and without you sharing any of your experience with me. My brain and body uses itself as a template to have a shared experience with you and the closer our life experiences internally have been, the more resonant we feel.

The story of

The story of  I was many things at ten years old, but one thing I wasn't was accepted. My family moved to a new town that summer—it was 1972—and on the first day of school when the school bell rang I stood in the middle of the girls’ line anxiously waiting to meet my new classmates. As I was studying my shoes I heard the laughter and the whispering, “What is that new boy doing in the girls line!” They were talking about me, well-dressed in boys clothing. I was humiliated, filled with shame, desperate to go back to my old school where people knew and accepted me. It was a long year of pain, accentuated by my teacher who routinely tried to force me to join the Girl Scouts.

I was many things at ten years old, but one thing I wasn't was accepted. My family moved to a new town that summer—it was 1972—and on the first day of school when the school bell rang I stood in the middle of the girls’ line anxiously waiting to meet my new classmates. As I was studying my shoes I heard the laughter and the whispering, “What is that new boy doing in the girls line!” They were talking about me, well-dressed in boys clothing. I was humiliated, filled with shame, desperate to go back to my old school where people knew and accepted me. It was a long year of pain, accentuated by my teacher who routinely tried to force me to join the Girl Scouts. This is where the story gets really interesting. The area that lit up when a subject was excluded is a strip of brain called the

This is where the story gets really interesting. The area that lit up when a subject was excluded is a strip of brain called the

killers flood your system buffering the pain. Neither of these reactions are under your conscious control. You are automatically protected.

killers flood your system buffering the pain. Neither of these reactions are under your conscious control. You are automatically protected.

In the last couple of years, more research has surfaced regarding LGBTQ elderly people, which provides a sobering look at their attitudes and thoughts about aging. The first and obvious concern is aging in a society and community that places a high value on youth, leaving the elderly feeling useless and insignificant (Fox, 2007). This is both within the LGBTQ communities and in the general population. Ageism is pervasive in the U.S.

In the last couple of years, more research has surfaced regarding LGBTQ elderly people, which provides a sobering look at their attitudes and thoughts about aging. The first and obvious concern is aging in a society and community that places a high value on youth, leaving the elderly feeling useless and insignificant (Fox, 2007). This is both within the LGBTQ communities and in the general population. Ageism is pervasive in the U.S.

Vita Sackville-West

Vita Sackville-West

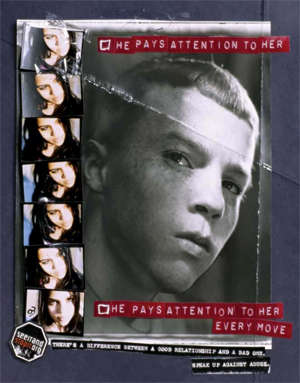

It’s important to talk with teens before they have sex. Research tells us that it is critical for teens to learn about sexual issues from a trusted adult before they have sex.

It’s important to talk with teens before they have sex. Research tells us that it is critical for teens to learn about sexual issues from a trusted adult before they have sex. capital. It was witnessing homelessness in her city that inspired her to figure out how she and her family could make a real difference, and her “power of half” principle has since become a movement.

capital. It was witnessing homelessness in her city that inspired her to figure out how she and her family could make a real difference, and her “power of half” principle has since become a movement.

human nervous system is literally wired to function best when in

human nervous system is literally wired to function best when in

academic success for students who have experienced early adversity and what classroom and therapeutic supports are most helpful for bolstering learning. Special education services for these students are provided by licensed teachers, dedicated and knowledgeable staff who have been trained in evidence-based approaches for PTSD treatment. Psychologists and educators are learning more about the elasticity of the brain and about efficacy for certain strength-based mental health supports, such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. Yet, there is much research to be done to understand how exactly these early traumatic experiences influence brain development and cognitive processes. In our initial collaborative investigation, presented at the

academic success for students who have experienced early adversity and what classroom and therapeutic supports are most helpful for bolstering learning. Special education services for these students are provided by licensed teachers, dedicated and knowledgeable staff who have been trained in evidence-based approaches for PTSD treatment. Psychologists and educators are learning more about the elasticity of the brain and about efficacy for certain strength-based mental health supports, such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. Yet, there is much research to be done to understand how exactly these early traumatic experiences influence brain development and cognitive processes. In our initial collaborative investigation, presented at the

Treating youth depression once it emerges may be much more distressing, and much less effective, than identifying early symptoms of illness and treating them before they develop into a full-blown disorder. Prevention approaches have the potential to reach a large number of adolescents, and may be more acceptable than treatment because services can be rendered in non-clinical settings (e.g., schools, primary care settings), and do not require adolescents to identify themselves as ill.

Treating youth depression once it emerges may be much more distressing, and much less effective, than identifying early symptoms of illness and treating them before they develop into a full-blown disorder. Prevention approaches have the potential to reach a large number of adolescents, and may be more acceptable than treatment because services can be rendered in non-clinical settings (e.g., schools, primary care settings), and do not require adolescents to identify themselves as ill.

wear away at our health and wellbeing. The NPR poll found that individuals with a chronic illness were more likely to report high stress in the previous month (36% compared to 26% overall), as were individuals living in poverty (36%) and single parents (35%). These chronic stressors tax our abilities to cope with stress. For those individuals with high levels of stress, problems with finances was one of the main sources of stress, and this was especially true for those

wear away at our health and wellbeing. The NPR poll found that individuals with a chronic illness were more likely to report high stress in the previous month (36% compared to 26% overall), as were individuals living in poverty (36%) and single parents (35%). These chronic stressors tax our abilities to cope with stress. For those individuals with high levels of stress, problems with finances was one of the main sources of stress, and this was especially true for those

Media coverage about social media has not been kind—often linking its use with cyberbullying, sexual predators, and depression or loneliness. But recent scholarship on new media demonstrates that interpersonal communication, online and offline, plays a vital role in integrating people into their communities by helping them build support, maintain ties, and promote trust. Social media is often used to escape from the pressures of life and alter moods, to secure an audience for self-disclosures, and to widen social networks and increase social capital. The

Media coverage about social media has not been kind—often linking its use with cyberbullying, sexual predators, and depression or loneliness. But recent scholarship on new media demonstrates that interpersonal communication, online and offline, plays a vital role in integrating people into their communities by helping them build support, maintain ties, and promote trust. Social media is often used to escape from the pressures of life and alter moods, to secure an audience for self-disclosures, and to widen social networks and increase social capital. The

Jen Dirga

Jen Dirga Sallie Dunning

Sallie Dunning As an integral creative spirit within the Black Arts Movement of the late 1960s and early 1970s, Dr. Angelou’s works of autobiography then poetry helped lay the foundation for Black women’s literature and literary studies, as well as Black feminist and womanist activism today. By laying bare her story, she made it possible to talk publicly and politically about many women’s issues that we now address through organized social movements – rape, incest, child sexual abuse, commercial sexual exploitation, domestic violence, and intimate partner violence. Through the acknowledgement of lesbianism in her writings as well as her public friendship with Black gay writer and activist James Baldwin, she helped shift America’s ability to envision and enact civil rights advances for the LGBTQ community. And the time she spent in Ghana during the early 1960s (where she met W.E.B. DuBois and made friends with Malcolm X, among others), helped Americans of all colors draw connections between the civil rights and Black Power movements in the U.S. and the decolonial independence and Pan-African movements of Africa and the diaspora.

As an integral creative spirit within the Black Arts Movement of the late 1960s and early 1970s, Dr. Angelou’s works of autobiography then poetry helped lay the foundation for Black women’s literature and literary studies, as well as Black feminist and womanist activism today. By laying bare her story, she made it possible to talk publicly and politically about many women’s issues that we now address through organized social movements – rape, incest, child sexual abuse, commercial sexual exploitation, domestic violence, and intimate partner violence. Through the acknowledgement of lesbianism in her writings as well as her public friendship with Black gay writer and activist James Baldwin, she helped shift America’s ability to envision and enact civil rights advances for the LGBTQ community. And the time she spent in Ghana during the early 1960s (where she met W.E.B. DuBois and made friends with Malcolm X, among others), helped Americans of all colors draw connections between the civil rights and Black Power movements in the U.S. and the decolonial independence and Pan-African movements of Africa and the diaspora.

In Mississippi, advocacy for low-income women and children tends to occur only in the non-profit and non-governmental sectors, which are both relatively under-resourced in comparison with other states. No adequately powerful counter-voice exists to offset the public tone of hostility toward low-income women. Further, conscious and sub-conscious racism is so entrenched in Mississippi that even policies that would appear to address racial discrimination turn out to have no impact. Mississippi could be said to be “Ground Zero” for structural racism. So intractable is this form of racism at all class levels that the elimination of

In Mississippi, advocacy for low-income women and children tends to occur only in the non-profit and non-governmental sectors, which are both relatively under-resourced in comparison with other states. No adequately powerful counter-voice exists to offset the public tone of hostility toward low-income women. Further, conscious and sub-conscious racism is so entrenched in Mississippi that even policies that would appear to address racial discrimination turn out to have no impact. Mississippi could be said to be “Ground Zero” for structural racism. So intractable is this form of racism at all class levels that the elimination of

The Commission also stated that the post-2015 development agenda must include gender-specific targets across other development goals, strategies, and objectives -- especially those related to education, health, economic justice, and the environment. It also called on governments to address the discriminatory social norms and practices that foster gender inequality, including early and forced marriage and other forms of violence against women and girls, and to strengthen accountability mechanisms for women's human rights.

The Commission also stated that the post-2015 development agenda must include gender-specific targets across other development goals, strategies, and objectives -- especially those related to education, health, economic justice, and the environment. It also called on governments to address the discriminatory social norms and practices that foster gender inequality, including early and forced marriage and other forms of violence against women and girls, and to strengthen accountability mechanisms for women's human rights.

In my hometown, I see evidence that women are emerging as confident, enthusiastic leaders of technology. Recently, I was at a public meeting for a community group planning the inaugural

In my hometown, I see evidence that women are emerging as confident, enthusiastic leaders of technology. Recently, I was at a public meeting for a community group planning the inaugural

At the

At the  Yet just because women weren’t holding high-profile leadership positions on campus didn’t mean that they weren’t contributing to campus life. The committee also found that women were more likely to “hold behind-the-scenes positions or seek to make a difference outside of elected office in campus groups.” Women at Princeton, for example, were often engaged in cause-based issues, like spearheading campaigns to institute recycling across campus.

Yet just because women weren’t holding high-profile leadership positions on campus didn’t mean that they weren’t contributing to campus life. The committee also found that women were more likely to “hold behind-the-scenes positions or seek to make a difference outside of elected office in campus groups.” Women at Princeton, for example, were often engaged in cause-based issues, like spearheading campaigns to institute recycling across campus. Second, the PPLA explores ways to do teaching and research that is driven by our values. We focus on the kinds of leadership and collective capacity we need to meet the common challenges our society face in a just way. We insist upon rigor and methodological soundness in our work, but we cannot separate moral and ethical considerations from our research and writing. Many scholars believe that our values suffuse our classrooms, laboratories, articles, and books whether we recognize and foreground them or not. The Project on Public Leadership seeks ways to affirm and support explicitly values-driven work.

Second, the PPLA explores ways to do teaching and research that is driven by our values. We focus on the kinds of leadership and collective capacity we need to meet the common challenges our society face in a just way. We insist upon rigor and methodological soundness in our work, but we cannot separate moral and ethical considerations from our research and writing. Many scholars believe that our values suffuse our classrooms, laboratories, articles, and books whether we recognize and foreground them or not. The Project on Public Leadership seeks ways to affirm and support explicitly values-driven work.

s a precursor to teen dating violence. Schools—where most young people meet, hang out, and develop patterns of social interactions—may be training grounds for domestic violence because behaviors conducted in public may provide license to proceed in private.

s a precursor to teen dating violence. Schools—where most young people meet, hang out, and develop patterns of social interactions—may be training grounds for domestic violence because behaviors conducted in public may provide license to proceed in private. But how do recruiters on the front-end value a varsity credential? Does sports participation in college, for example, offer access to enter a corporate career?

But how do recruiters on the front-end value a varsity credential? Does sports participation in college, for example, offer access to enter a corporate career?

Utilizing such “rape myths” like the need for well-lit streets and women’s ability to walk safely perfectly illustrates Haugen’s limited understanding of sexual violence:

Utilizing such “rape myths” like the need for well-lit streets and women’s ability to walk safely perfectly illustrates Haugen’s limited understanding of sexual violence:

one of the few surviving ‘Kinder.’ It was a somber occasion, both a tribute to the courage of those who survived and the generosity of the (mostly non-Jewish) families that took these children into their homes and raised them.

one of the few surviving ‘Kinder.’ It was a somber occasion, both a tribute to the courage of those who survived and the generosity of the (mostly non-Jewish) families that took these children into their homes and raised them. A week before my trip she informed me a Stolperstein for Marie Driesen was already in place, and that its installation had been arranged by a current owner of an apartment at the Schoeneberg address. Two weeks later my husband and I were warmly greeted by Hannelore and the owner, Baerbel. We looked at the Stolperstein in the sidewalk, and then sat at a table in Baerbel’s apartment and talked. We learned that around 1938, 37-39 Belziger Strasse had been designated as a Jewish building. This meant that all Jewish residents in the building were forced to take in other Jews as lodgers, and Jews from other buildings were forced to move into the apartments; measures that made it easier for them to be rounded up later. Baerbel, a retired geologist, had worked tirelessly to obtain documents on the 22 Jewish residents taken from that building, and she had a huge binder with files on each one. But she went further; she asked the 52 current residents to contribute to the cost of installing Stolperstein for them. Not a single person refused, and the installation had been filmed by local television.

A week before my trip she informed me a Stolperstein for Marie Driesen was already in place, and that its installation had been arranged by a current owner of an apartment at the Schoeneberg address. Two weeks later my husband and I were warmly greeted by Hannelore and the owner, Baerbel. We looked at the Stolperstein in the sidewalk, and then sat at a table in Baerbel’s apartment and talked. We learned that around 1938, 37-39 Belziger Strasse had been designated as a Jewish building. This meant that all Jewish residents in the building were forced to take in other Jews as lodgers, and Jews from other buildings were forced to move into the apartments; measures that made it easier for them to be rounded up later. Baerbel, a retired geologist, had worked tirelessly to obtain documents on the 22 Jewish residents taken from that building, and she had a huge binder with files on each one. But she went further; she asked the 52 current residents to contribute to the cost of installing Stolperstein for them. Not a single person refused, and the installation had been filmed by local television.

Just because we don’t all work for social change organizations, however, doesn’t mean there aren’t major ways we can make each a difference. What do you care about? What change would you like to see in the world? As great and necessary as organizations are in the social change equation, they are not the end-all and be-all. Individuals and small groups, even when they are working for change outside formal organizations, can make a monumental difference in outcomes for many through partnering, advocacy, endorsement, and financial support. As

Just because we don’t all work for social change organizations, however, doesn’t mean there aren’t major ways we can make each a difference. What do you care about? What change would you like to see in the world? As great and necessary as organizations are in the social change equation, they are not the end-all and be-all. Individuals and small groups, even when they are working for change outside formal organizations, can make a monumental difference in outcomes for many through partnering, advocacy, endorsement, and financial support. As

But for a single mother, even this culturally permissible deviance is insufficient. My life with Amy is different from the lives of most of my colleagues and friends. I could not provide emotional, physical and financial support for Amy without re-envisioning motherhood. Amy and I have lived with a shifting assortment of male and female students, single women as well as married women with children. Work for me is not possible without round the clock care for Amy. This is true for all mothers and children, but it is a need that is normally outgrown. Not so in our case. Amy fuels my passion for feminist solutions; not simply for childcare, but for policy issues across the board. I know first hand too many of the dilemmas confronting women, from the mostly invisible, predominately female workers who care for others in exchange for poverty level wages to successful business women struggling to be perfect mothers, perfect wives and powerfully perfect CEOs.

But for a single mother, even this culturally permissible deviance is insufficient. My life with Amy is different from the lives of most of my colleagues and friends. I could not provide emotional, physical and financial support for Amy without re-envisioning motherhood. Amy and I have lived with a shifting assortment of male and female students, single women as well as married women with children. Work for me is not possible without round the clock care for Amy. This is true for all mothers and children, but it is a need that is normally outgrown. Not so in our case. Amy fuels my passion for feminist solutions; not simply for childcare, but for policy issues across the board. I know first hand too many of the dilemmas confronting women, from the mostly invisible, predominately female workers who care for others in exchange for poverty level wages to successful business women struggling to be perfect mothers, perfect wives and powerfully perfect CEOs.