Beginning in the mid-1990s, with my colleague, Benjamin E. Saunders, Ph.D., of the Medical University of South Carolina, and a team of researchers, I conducted an assessment study of family violence and functioning with 530 families from 12 naval bases who had been reported to the US Navy's Family Advocacy Program due to allegations of child sexual abuse, child physical abuse, or intimate partner violence. We interviewed parents (one of whom was a Navy servicemember) and children in a longitudinal study of interventions and outcomes.

Beginning in the mid-1990s, with my colleague, Benjamin E. Saunders, Ph.D., of the Medical University of South Carolina, and a team of researchers, I conducted an assessment study of family violence and functioning with 530 families from 12 naval bases who had been reported to the US Navy's Family Advocacy Program due to allegations of child sexual abuse, child physical abuse, or intimate partner violence. We interviewed parents (one of whom was a Navy servicemember) and children in a longitudinal study of interventions and outcomes. This study was designed to help Navy leaders develop and refine the Family Advocacy Program. It was a critical, long-term effort to positively affect how the Navy responds to family violence among its servicemembers, and therefore to improve the lives of women, children, and families.

More recently, we re-examined some of the myriad of data to understand more about the predictors of children’s tendency to blame themselves for child abuse and intimate partner violence. We had gathered important longitudinal data from 195 of the children (aged 7-17) on their reported self-blame tendencies (e.g., Do you blame yourself when things go wrong?), the frequency of parent-child conflict (e.g., yelling, threatening), and depressive symptoms. We had also conducted semi-structured interviews to assess the children’s victimization experiences, including the type, injury, and number of perpetrators. Baseline data was collected 2-6 weeks after the initial report; self-blame was reported again after 9-12 months and 18-24 months.

My coauthors—Caitlin Rancher, Ph.D., Rochelle Hanson, Ph.D., Benjamin E. Saunders, Ph.D., and Daniel W. Smith, Ph.D.—and I published a paper from the study in the journal Child Abuse & Neglect in January 2024.

We found that in general, children who reported higher levels of parent-child conflict and depressive symptoms at baseline expressed increased self-blame over the next two years. Such self-blame has been identified as an important consequence of child maltreatment that can contribute to later psychological and behavioral problems. Understanding more about which children will develop self-blame following victimization has important implications for families, professionals who work with these children, policymakers, and military leadership.

Enter Military REACH, an organization whose goal is to put important research into the hands of folks who can use it. Military REACH summarizes newly published studies related to the wellbeing of military families and distributes them directly to the Department of Defense's Office of Military Community and Family Policy. They also distribute their products to researchers, helping professionals, and others interested in military family research.

Military REACH recently featured our study in their newsletter, highlighting the following implications for the folks mentioned above:

Implications for Families:

- Explain to children and adolescents, especially after an allegation of child abuse or intimate partner violence, that family violence is not their fault.

- Know the signs of child abuse and neglect. If you suspect abuse, report your concerns.

Implications for Helping Professionals:

- Complete a robust childhood trauma history to understand the scope of experiences of children and adolescents whose families are referred to the Family Advocacy Program.

Implications for Policymakers and Military Leadership

- Ensure the military community understands how to report suspected victimization and the importance of speaking up.

- Equip child advocates with the tools to engage effectively with children and families, including immediate safety assessments and ongoing assessments of mental health and wellbeing that include perceptions of self-blame and locus of control.

When we pursue research studies, our hope is always to turn our research into action and to improve the lives of those affected—even long after the study ends. Military REACH and other similar organizations play significant roles in making this happen. With their help, we can work to ensure children do not blame themselves for violence that occurs in their families.

Linda M. Williams, Ph.D., is director of the Justice and Gender-Based Violence Research Initiative at the Wellesley Centers for Women.

Dear Friends of WCW:

Dear Friends of WCW:

Senior Research Scientist

Senior Research Scientist  April is Sexual Assault Awareness Month and Child Abuse Prevention Month. Over the years, our work at WCW has addressed a wide range of critical issues related to these topics. One of the lesser publicly understood issues is the pressing problem of commercial sexual exploitation of children (CSEC) and teens, also known as sex trafficking.

April is Sexual Assault Awareness Month and Child Abuse Prevention Month. Over the years, our work at WCW has addressed a wide range of critical issues related to these topics. One of the lesser publicly understood issues is the pressing problem of commercial sexual exploitation of children (CSEC) and teens, also known as sex trafficking.

Sage Carson was raped by a graduate student in her sophomore year of college. In an article for

Sage Carson was raped by a graduate student in her sophomore year of college. In an article for  In 2019, Melissa Morabito, Ph.D.,

In 2019, Melissa Morabito, Ph.D.,  Victims of Domestic Violence Often Face Housing Problems

Victims of Domestic Violence Often Face Housing Problems

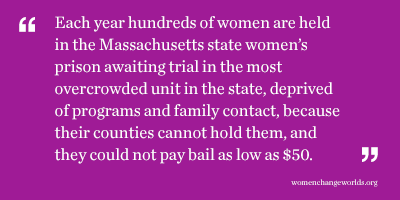

form of justice-involvement (mostly probation). However, comparisons between justice-involved and non-justice-involved women revealed few differences on demographic and other characteristics. For example, their ages, maternal status, the number of children they have, their children’s ages, and the percentage living with their children.

form of justice-involvement (mostly probation). However, comparisons between justice-involved and non-justice-involved women revealed few differences on demographic and other characteristics. For example, their ages, maternal status, the number of children they have, their children’s ages, and the percentage living with their children.

Thirty-six years later, the social status of LGBT people has changed enormously. Few LGBT people in Montana, say, would worry that a march in Washington, DC, would cause them to be set upon by an angry mob. In liberal Massachusetts, my employer, my neighbors, and my doctor all know I’m a lesbian. I’ve been married to my partner of 27 years since 2003—and my entire family came to our wedding. Since the Supreme Court’s Obergefell decision in June, my marriage is recognized by the federal government as well as that of my state. I can watch many television shows and movies in which LGBT characters make it through the entire plot without killing themselves. I can kiss my wife goodbye on the front steps when I leave for work in the morning without worrying (too much) that we’ll be beaten or shot.

Thirty-six years later, the social status of LGBT people has changed enormously. Few LGBT people in Montana, say, would worry that a march in Washington, DC, would cause them to be set upon by an angry mob. In liberal Massachusetts, my employer, my neighbors, and my doctor all know I’m a lesbian. I’ve been married to my partner of 27 years since 2003—and my entire family came to our wedding. Since the Supreme Court’s Obergefell decision in June, my marriage is recognized by the federal government as well as that of my state. I can watch many television shows and movies in which LGBT characters make it through the entire plot without killing themselves. I can kiss my wife goodbye on the front steps when I leave for work in the morning without worrying (too much) that we’ll be beaten or shot. Still, as

Still, as

Although these are all big questions, I have at least learned a few things over the years through my

Although these are all big questions, I have at least learned a few things over the years through my  Lisa Fortuna

Lisa Fortuna

The story of

The story of  capital. It was witnessing homelessness in her city that inspired her to figure out how she and her family could make a real difference, and her “power of half” principle has since become a movement.

capital. It was witnessing homelessness in her city that inspired her to figure out how she and her family could make a real difference, and her “power of half” principle has since become a movement.

Utilizing such “rape myths” like the need for well-lit streets and women’s ability to walk safely perfectly illustrates Haugen’s limited understanding of sexual violence:

Utilizing such “rape myths” like the need for well-lit streets and women’s ability to walk safely perfectly illustrates Haugen’s limited understanding of sexual violence:

A model for human experience that emphasizes our separateness works against our sense of basic connection and belonging. It leads us to believe that we should function autonomously in situations where that is impossible. By placing unattainable standards of individualism on us, it leaves us vulnerable to feeling even more inadequate, ashamed, and stressed out. There is abundant data that social ties are decreasing in the U.S.; more and more people feel they can trust no one. (Putnam, R. 2000 Bowling Alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York: Simon and Schuster.) And traditional psychology with its overemphasis on internal, individual problems contributes to our failure, at a societal level, to invest in social justice and social support programs. Rather than addressing the problems in a society that disempower us and perpetuate systems of injustice, we have tended to locate the problems in the individual.

A model for human experience that emphasizes our separateness works against our sense of basic connection and belonging. It leads us to believe that we should function autonomously in situations where that is impossible. By placing unattainable standards of individualism on us, it leaves us vulnerable to feeling even more inadequate, ashamed, and stressed out. There is abundant data that social ties are decreasing in the U.S.; more and more people feel they can trust no one. (Putnam, R. 2000 Bowling Alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York: Simon and Schuster.) And traditional psychology with its overemphasis on internal, individual problems contributes to our failure, at a societal level, to invest in social justice and social support programs. Rather than addressing the problems in a society that disempower us and perpetuate systems of injustice, we have tended to locate the problems in the individual.

All day I wondered how the class had responded to the film. I was worried, but the description of the discussion surpassed my expectations. I called the teacher to thank her. She said that they had been working on stereotypes and biases for several weeks but it wasn’t until kids who were classmates talked about their own experience that opinions and attitudes shifted. This was before standardized testing and she was a brilliant teacher who made time for this important discussion. I know there are many brilliant teachers who could create spaces for tolerance in their classrooms if given some tools and language to guide them.

All day I wondered how the class had responded to the film. I was worried, but the description of the discussion surpassed my expectations. I called the teacher to thank her. She said that they had been working on stereotypes and biases for several weeks but it wasn’t until kids who were classmates talked about their own experience that opinions and attitudes shifted. This was before standardized testing and she was a brilliant teacher who made time for this important discussion. I know there are many brilliant teachers who could create spaces for tolerance in their classrooms if given some tools and language to guide them.

Part II: Social Scientific Perspectives on Making Change in America

Part II: Social Scientific Perspectives on Making Change in America Depression is more epidemic than the common cold, and we hear more and more about such issues as bipolar disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, and suicide. On the one hand, we have begun to recognize a connection between mental ibellness and certain forms of violence – and while mental illness certainly doesn’t explain all forms of violence in America, it raises our level of concern about why people experience mental illness and whether we are doing enough about it. Fortunately, the Affordable Care Act will make

Depression is more epidemic than the common cold, and we hear more and more about such issues as bipolar disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, and suicide. On the one hand, we have begun to recognize a connection between mental ibellness and certain forms of violence – and while mental illness certainly doesn’t explain all forms of violence in America, it raises our level of concern about why people experience mental illness and whether we are doing enough about it. Fortunately, the Affordable Care Act will make

During the flight home, as I reviewed the day’s

During the flight home, as I reviewed the day’s

What can a good-looking, white woman with a Smith College degree and middle-class upbringing teach us about prisons in America?

What can a good-looking, white woman with a Smith College degree and middle-class upbringing teach us about prisons in America? These lessons are realized just a few weeks before her scheduled release date, when she encounters Norma in the Chicago Correctional Center where she has been transported by “Con Air” to give testimony against another major player in the drug scheme. She overcomes her anger at Norma’s betrayal as together they cope with conditions far worse than the federal prisons from which they have come. In the Correctional Center, Kerman is horrified by the ‘crazy’ women and indifferent staff; the idleness and lack of daily structure; lack of daylight and exercise; inedible food and filthy conditions; and the inability to escape the constant noise and light.

These lessons are realized just a few weeks before her scheduled release date, when she encounters Norma in the Chicago Correctional Center where she has been transported by “Con Air” to give testimony against another major player in the drug scheme. She overcomes her anger at Norma’s betrayal as together they cope with conditions far worse than the federal prisons from which they have come. In the Correctional Center, Kerman is horrified by the ‘crazy’ women and indifferent staff; the idleness and lack of daily structure; lack of daylight and exercise; inedible food and filthy conditions; and the inability to escape the constant noise and light.

We have waited too long! In 1994, governments agreed to an ambitious

We have waited too long! In 1994, governments agreed to an ambitious

life-changing impact of our own

life-changing impact of our own

trauma; lack of education and training; sexual victimization by criminal justice personnel; and restricted eligibility for state benefits.

trauma; lack of education and training; sexual victimization by criminal justice personnel; and restricted eligibility for state benefits.

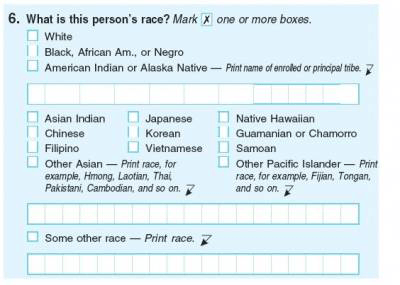

media; compelling stage models have been proposed first by Poston (1990) and then expanded by Kerwin and Ponterotto (1995). In addition, Fhagen-Smith’s (2003) WCW Working Paper also described a stage model of mixed ancestry identity development. Children grow up taking on the identity community to them by their immediate family for the most part, although

media; compelling stage models have been proposed first by Poston (1990) and then expanded by Kerwin and Ponterotto (1995). In addition, Fhagen-Smith’s (2003) WCW Working Paper also described a stage model of mixed ancestry identity development. Children grow up taking on the identity community to them by their immediate family for the most part, although