Nearly 5 million college students in the U.S. are raising children, and almost three-quarters of undergraduate students with dependent children are mothers. These mothers face significant barriers to completing their degrees, and part of what makes it challenging to advocate for them is that colleges rarely count how large their population is on campus or track their educational outcomes. Though some data exists at the federal level, it’s difficult to use it to draw specific insights about demographics at the campus, district, system, or state level.

Nearly 5 million college students in the U.S. are raising children, and almost three-quarters of undergraduate students with dependent children are mothers. These mothers face significant barriers to completing their degrees, and part of what makes it challenging to advocate for them is that colleges rarely count how large their population is on campus or track their educational outcomes. Though some data exists at the federal level, it’s difficult to use it to draw specific insights about demographics at the campus, district, system, or state level.

When student mothers aren’t counted on campus, they don’t get the resources they need, and they feel invisible to boot.

Without data on student mothers, it’s more difficult for college administrators to establish, fund, and sustain supportive strategies and programs—things like child care, family housing, or parenting student resource centers, which are critical to helping student mothers graduate. I have met with parenting students from across the country who have been told by their colleges that they cannot justify expanded programs and support without the data.

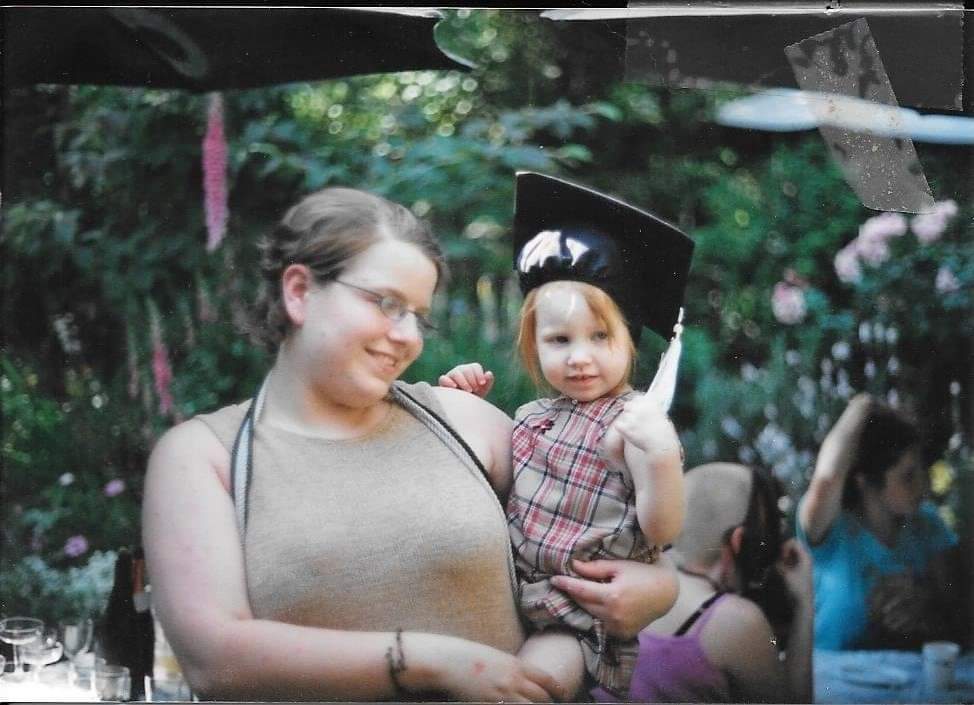

In the past few years, advocates have made significant in-roads on gathering this data. In May 2021, Oregon and Illinois both passed legislation requiring that public institutions of higher education (IHEs), including community colleges and public universities, begin collecting data on parenting status. As both director of WCW’s Higher Education Access for Parenting Students Research Initiative, and an Oregonian student parent alumna, I helped organize the campaign for the Oregon legislation, and testified in support of the bill as an expert witness. My father and both my children also submitted written testimony, together representing three generations of Oregonian parenting students.

Groups of higher education leaders from several states are currently exploring how parenting status demographics could be incorporated within their institutional research data systems, and what’s needed to make these strategies viable.

To start, we know that questions pertaining to parenting students need to be incorporated into existing data systems, so they are easily accessible to parenting students. While voluntary surveys can be helpful tools for following up, it can be hard for student mothers to find time to respond to them. It’s a lot easier to respond to a few extra questions on a form they were already completing, or a pop-up window that opens when they log in to register for their classes. Higher response rates lead to more accurate data.

Data systems aren’t just about collection, though; data also need to be used effectively. In Oregon and Illinois, public IHEs are required to share parenting status data with their state’s higher education authority every year. If concerns are observed, the state higher education authority could issue recommendations or requirements to colleges or universities, ask the legislature to issue further directives, or request funding allocations.

Data is powerful when it comes to parenting students. Programs like student child care have heavily relied on parenting student enrollment data to make the case for grants and internal budget allocations. For example, the federal Child Care Access Means Parents in School Program (CCAMPIS), which subsidizes child care for low-income parents in college, requires IHEs to provide data on parenting student enrollment and estimated need for child care to qualify for funding. And most IHEs that offer parenting student services and child care subsidies supported by student fees have reported that collecting data helped make their case for funding to the committees that determine how student fee dollars are allocated.

Most IHEs that have obtained access to this data have partnered with their financial aid offices to pull aggregate enrollment numbers from the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) system. The FAFSA form, which all students are required to complete to qualify for federal student aid, includes questions about dependent children. But it offers an incomplete picture: According to one recent report, 1.7 million high school graduates didn’t even file the FAFSA in the 2020-21 school year. Imagine how much more support might be possible with better data.

And this is just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to useful data—ideally, we should follow student parents throughout their college careers to understand what helps them be successful and what places obstacles in their path. Parenting students’ GPAs reflect academic achievement that is on par with their non-parenting peers, but very few graduate on time, and most stop in and out of college multiple times before earning their degrees. It’s important not just to count how many parenting students there are, but also to track their retention and graduation rates and other outcomes to ensure educational equity. Student mothers are disproportionately represented among diverse populations, and the data systems being developed in Oregon and Illinois will be capable of disaggregating and identifying groups that might need specialized support to stay in college and graduate.

When student mothers succeed in college, it has a ripple effect. It instills in their children the value of education and puts their families and communities on a path to economic security. My mom, who passed away a few years ago but was a student parent herself, would remind me to mention that educating mothers is also critical to democracy and shaping an informed electorate. Ample research, including a recent study by my colleague and research partner Dr. Theresa Anderson, has found that children who witness their mothers attend college have better academic outcomes overall. But even though kids do better in school, they also have more behavioral and health challenges, in part because their mothers are stressed and time stretched, and need to be better supported.

Counting student mothers (and all parenting students) and their children in higher education data helps college and university administrators acknowledge and see them, and in the long run can be a catalyst for programs and services to better support them. Let’s help them be seen, and succeed, by showing them they matter.

Autumn Green, Ph.D., is a research scientist at the Wellesley Centers for Women studying higher education access for parenting students. Her Data-to-Action Campaign for Parenting Student Success aims to identify the most effective strategies for implementing data tracking and reporting systems that identify parenting students enrolled in college, as well as follow their educational outcomes like grades, retention, and graduation.

, Ph.D., is a research scientist at the Wellesley Centers for Women studying

, Ph.D., is a research scientist at the Wellesley Centers for Women studying

Last year on Mother's Day, I was driving through the Rocky Mountains, on my way from Oregon to Maine where my life was about to change forever. It was the first Mother's Day I had spent without my kids since they were born, and the first Mother's Day since my own mother had passed away. I yearned to call her to share the news of my latest adventure, as I always had during our frequent long-distance phone chats, but I knew I couldn’t. The following week, my daughter would bring my granddaughter into the world on the southern coast of Maine. The transcontinental journey I was on would end with the newest love of my life joining our family.

Last year on Mother's Day, I was driving through the Rocky Mountains, on my way from Oregon to Maine where my life was about to change forever. It was the first Mother's Day I had spent without my kids since they were born, and the first Mother's Day since my own mother had passed away. I yearned to call her to share the news of my latest adventure, as I always had during our frequent long-distance phone chats, but I knew I couldn’t. The following week, my daughter would bring my granddaughter into the world on the southern coast of Maine. The transcontinental journey I was on would end with the newest love of my life joining our family. Yesterday on route to work my phone exploded with messages from friends and colleagues urging me to, "Turn on NPR right now,” to hear their

Yesterday on route to work my phone exploded with messages from friends and colleagues urging me to, "Turn on NPR right now,” to hear their  “Someday you will go to college, too,” a young mother tells her eight year old son at her baccalaureate graduation ceremony.

“Someday you will go to college, too,” a young mother tells her eight year old son at her baccalaureate graduation ceremony.