I was many things at ten years old, but one thing I wasn't was accepted. My family moved to a new town that summer—it was 1972—and on the first day of school when the school bell rang I stood in the middle of the girls’ line anxiously waiting to meet my new classmates. As I was studying my shoes I heard the laughter and the whispering, “What is that new boy doing in the girls line!” They were talking about me, well-dressed in boys clothing. I was humiliated, filled with shame, desperate to go back to my old school where people knew and accepted me. It was a long year of pain, accentuated by my teacher who routinely tried to force me to join the Girl Scouts.

I was many things at ten years old, but one thing I wasn't was accepted. My family moved to a new town that summer—it was 1972—and on the first day of school when the school bell rang I stood in the middle of the girls’ line anxiously waiting to meet my new classmates. As I was studying my shoes I heard the laughter and the whispering, “What is that new boy doing in the girls line!” They were talking about me, well-dressed in boys clothing. I was humiliated, filled with shame, desperate to go back to my old school where people knew and accepted me. It was a long year of pain, accentuated by my teacher who routinely tried to force me to join the Girl Scouts.

This memory popped back into my mind when I first discovered social pain overlap theory (SPOT) by Eisenberger and Lieberman at UCLA. These researchers study the brain in social situations. They devised a clever experiment during which people were asked to join a virtual cyberball game on a computer screen. As the game progresses, the research subject is attached to a functional brain imaging machine. Now, being left out of a cyberball toss experiment where you do not even know or see the other players is nothing compared to my year of ridicule and ostracism in fifth grade, nor does it compare to the many forms of being socially rejected from bullying, to racism and homophobia, but still, this rather mild social exclusion told these researchers something very important: Being left out hurts most people. They feel uncomfortable, unsettled, irritated… distressed. The next step was to see what area of the brain was activated with this distress.

This is where the story gets really interesting. The area that lit up when a subject was excluded is a strip of brain called the dorsal anterior cingulate gyrus (dACC). The dACC already had been mapped as the area of the brain that is activated when a person is distressed by physical pain. To humans, being socially excluded is so important that it uses the same neurological pathways used to register when you are in danger from a physical injury or illness. Remember the old saying, “sticks and stones will break your bones and names will never hurt you”? Not true. It should have been “sticks and stones will break you bones and names will hurt you too!”

This is where the story gets really interesting. The area that lit up when a subject was excluded is a strip of brain called the dorsal anterior cingulate gyrus (dACC). The dACC already had been mapped as the area of the brain that is activated when a person is distressed by physical pain. To humans, being socially excluded is so important that it uses the same neurological pathways used to register when you are in danger from a physical injury or illness. Remember the old saying, “sticks and stones will break your bones and names will never hurt you”? Not true. It should have been “sticks and stones will break you bones and names will hurt you too!”

The human nervous system has evolved to be held within the safety of safe relationships. When we drift away from our group or are pushed out, when we are ridiculed, bullied, or shunned it creates real pain. This happens to individuals within groups and to groups of people within the larger society. SPOT theory confirms that people who live in glass houses shouldn’t throw stones—but it also tells us that we all live in glass houses, we are all vulnerable to the pain of being left out. It is simply how we are wired.

Amy Banks, M.D., has devoted her career to understanding the neurobiology of relationships. She was an instructor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and is the Director of Advanced Training at the Jean Baker Miller Training Institute (JBMTI) at the Wellesley Centers for Women at Wellesley College. She is the author with Leigh Ann Hirschman of the forthcoming book, Four Ways to Click: Rewire your Brain for Stronger, More Rewarding Relationships (Penguin Random House).

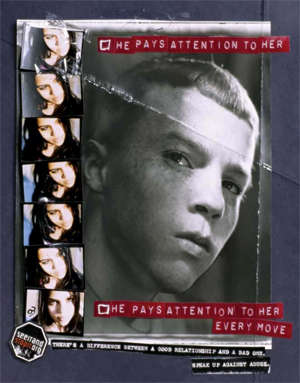

s a precursor to teen dating violence. Schools—where most young people meet, hang out, and develop patterns of social interactions—may be training grounds for domestic violence because behaviors conducted in public may provide license to proceed in private.

s a precursor to teen dating violence. Schools—where most young people meet, hang out, and develop patterns of social interactions—may be training grounds for domestic violence because behaviors conducted in public may provide license to proceed in private.

Students are always watching. They are watching adults at their best and they are particularly watching adults when they are in conflict. While emphasis and expectations of behavior is often placed on the students, adults in schools should remember to take a step back and look at themselves, their relationships, and the behaviors students see them model. It’s imperative that adult communities in schools reflect the same expectations of behavior that we have for students. Otherwise a climate may develop where students and adults may not feel safe to identify, report, and effectively address bullying behavior.

Students are always watching. They are watching adults at their best and they are particularly watching adults when they are in conflict. While emphasis and expectations of behavior is often placed on the students, adults in schools should remember to take a step back and look at themselves, their relationships, and the behaviors students see them model. It’s imperative that adult communities in schools reflect the same expectations of behavior that we have for students. Otherwise a climate may develop where students and adults may not feel safe to identify, report, and effectively address bullying behavior.