The fifth-grader’s voice was full of emotion as he shouted, “That’s not fair! What a mean thing to do!”

The fifth-grader’s voice was full of emotion as he shouted, “That’s not fair! What a mean thing to do!”

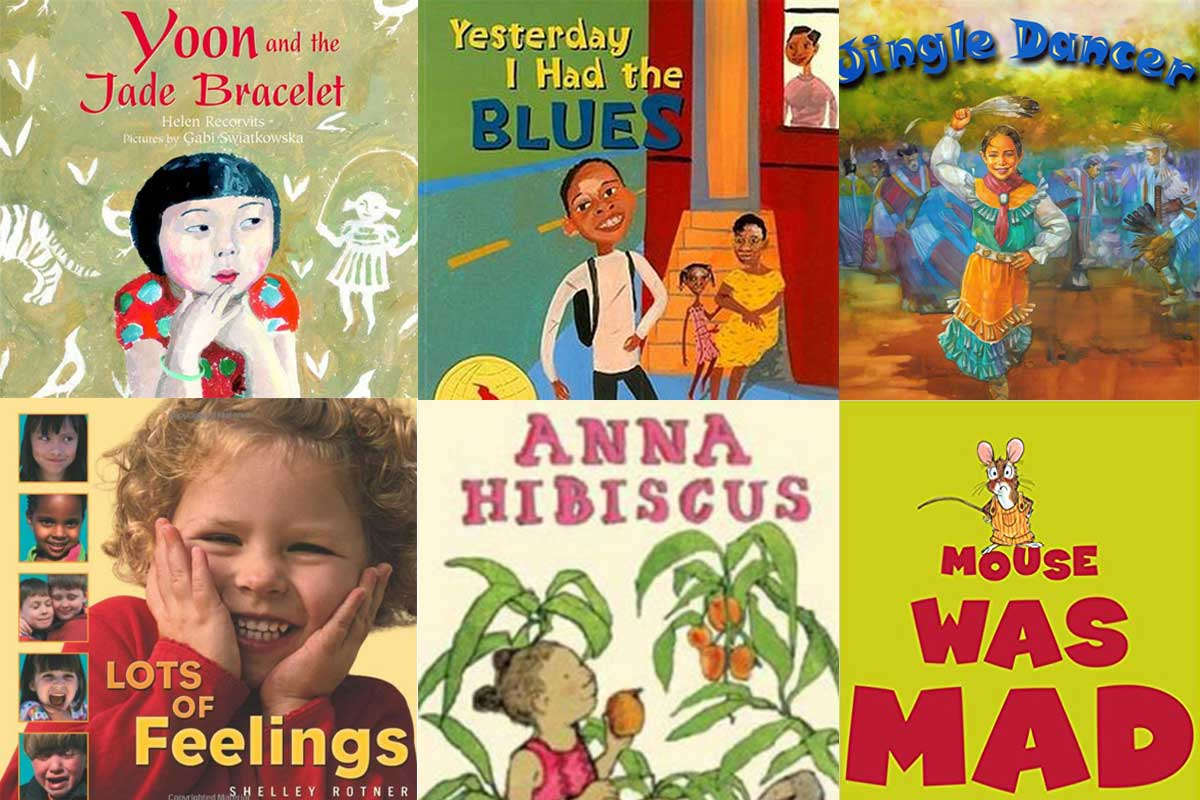

He wasn’t upset about an event on the playground, or on the school bus. This student was reacting to an incident described in a picture book entitled Yoon and the Jade Bracelet, by Helen Recorvits. As other students chimed in, the teacher took the opportunity to facilitate a discussion about peer mistreatment, how it feels to be left out, and the role of bystanders. Students expressed genuine concern for Yoon, the main character in the story. Throughout this time of authentic connection to each other and the story, the teacher and his students focused on some key social and emotional skills, such as recognizing and naming feelings, perspective-taking, and empathy. The combination of the book, the teacher, and the children created the equivalent of an electrical current that energized an authentic conversation about how people choose to treat each other.

The Collaborative for Academic, Social and Emotional Learning (CASEL) identifies the following social competency skills as keys to success in school and beyond: self-awareness, self-management, social awareness/empathy, relationship skills, and responsible decision-making. Social and emotional learning (SEL) skills can be taught to children in schools through programs such as Open Circle, a program of the Wellesley Centers for Women, which uses children’s literature as a vital part of its curriculum.

Whether books are shared in a classroom, a public library, or a living room, there are some specific ways that educators and caregivers can leverage the emotional connection between children and literature to reinforce SEL skills, including empathy. Some people may make a New Year’s resolution to read more books; I encourage us all to include children in this goal. Here are five ways to support SEL skills through children’s literature:

1. Help children build their feelings vocabulary.

The most basic building block for social competency is self-awareness, being able to recognize and name your emotions. Sharing picture books that highlight a range of emotions, such as Lots of Feelings, by Shelley Rotner, or Yesterday I Had the Blues, by Jeron Ashford Frame, helps children expand their feelings vocabulary and recognize that it’s normal to have many different feelings, including negative ones.

2. Model and reinforce self-management strategies.

It’s important for children to know that they can learn some ways to calm down when they are upset. Books such as Sometimes I‘m Bombaloo, by Rachel Vail, or Mouse was Mad, by Linda Urban, illustrate effective self-management strategies. As you read aloud stories like these, share your own experiences with challenging feelings and describe your coping strategies. Encourage children to find strategies that work for them.

3. Choose books with diverse content.

Emily Style, a co-founder of the National SEED Project at the Wellesley Centers for Women, has written about how curriculum serves as both mirrors and windows for students. Sharing literature that is culturally diverse ensures that all children can see themselves reflected in books, and can see beyond their own world and experiences. Encourage children to explore the perspective of characters who are different from themselves in order to build their capacity for empathy. Books such as the Anna Hibiscus series by Atinuke, or Jingle Dancer, by Cynthia Leitich Smith, can dispel stereotypes and pave the way for building positive relationships and making responsible decisions about how we treat each other.

4. Use an interactive approach.

Megan Dowd Lambert, author of Reading Picture Books with Children: How to shake up storytime and get kids talking about what they see, emphasizes the importance of “reading with children as opposed to reading to them.”

Lambert suggests asking open-ended questions, such as: “What’s going on in this picture? What do you see that makes you say that?” Open-ended questions also help children connect to their experiences and feelings. For example, you might ask: “How do you think the character feels? What are some things that make you feel angry? (scared, upset, happy, etc.) or, “What might you have done differently if you were this character?” To help children develop consequential-thinking skills, ask them to predict what might happen when a character behaves a certain way or makes a particular choice.

5. Choose books children can connect with.

Anyone who has read with one child, or a group of children knows that literature engages both the heart and the mind. Pairing the right book with a child, and helping her explore personal connections to the story completes the circuit to power up social and emotional learning. For inspiration, get started by looking at Open Circle’s list of children’s books connected to SEL.

Peg Sawyer is a trainer and coach at Open Circle, a program of the Wellesley Centers for Women, that provides a unique, evidence-based social and emotional learning program for grades K-5.

Vita Sackville-West

Vita Sackville-West

publication because we had, basically, run out of money, WCW partnered with

publication because we had, basically, run out of money, WCW partnered with