September is National School Success month, a time when parents are focused on helping their children begin a positive start to the new school year. At this time I urge you to consider those children who, through no fault of their own, are struggling to succeed academically because of exposure to early adversity and trauma. WCW has begun a research partnership with The Home for Little Wanderers, a child and family services agency in Massachusetts that was founded in 1799 and provides a continuum of care for 4,000 children annually. Children served who are most at risk are those in foster care and/or enrolled in The Home’s residential educational settings. These students have experienced significant trauma and neglect, and have complex psychological and educational needs. Posttraumatic stress (PTSD) symptoms as a result of toxic stress may inhibit their capacity for learning, interfering with the ability to maintain attention, disrupting cognitive processes and memory, increasing hypervigilance and reactivity that present as behavioral problems, and too often leaving students with a feeling of hopelessness for the future. These are students at high risk for dropping out of school, despite their intellectual capabilities.

Together, the Wellesley Centers for Women (WCW) and The Home for Little Wanderers are dedicated to better understanding the barriers that get in the way of  academic success for students who have experienced early adversity and what classroom and therapeutic supports are most helpful for bolstering learning. Special education services for these students are provided by licensed teachers, dedicated and knowledgeable staff who have been trained in evidence-based approaches for PTSD treatment. Psychologists and educators are learning more about the elasticity of the brain and about efficacy for certain strength-based mental health supports, such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. Yet, there is much research to be done to understand how exactly these early traumatic experiences influence brain development and cognitive processes. In our initial collaborative investigation, presented at the American Psychological Association Annual Convention this past August, WCW and The Home researchers found that students with a greater number of various traumatic experiences also had more severe PTSD symptoms, and in addition, these PTSD symptoms were associated with students’ ratings of impairment in doing their schoolwork. Over time some students showed decreases in PTSD symptoms and its interference with schoolwork. As we move forward in our collaborative research, our aim is to increase knowledge about predictors of these patterns of improvement so that more students have opportunities for success.

academic success for students who have experienced early adversity and what classroom and therapeutic supports are most helpful for bolstering learning. Special education services for these students are provided by licensed teachers, dedicated and knowledgeable staff who have been trained in evidence-based approaches for PTSD treatment. Psychologists and educators are learning more about the elasticity of the brain and about efficacy for certain strength-based mental health supports, such as Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. Yet, there is much research to be done to understand how exactly these early traumatic experiences influence brain development and cognitive processes. In our initial collaborative investigation, presented at the American Psychological Association Annual Convention this past August, WCW and The Home researchers found that students with a greater number of various traumatic experiences also had more severe PTSD symptoms, and in addition, these PTSD symptoms were associated with students’ ratings of impairment in doing their schoolwork. Over time some students showed decreases in PTSD symptoms and its interference with schoolwork. As we move forward in our collaborative research, our aim is to increase knowledge about predictors of these patterns of improvement so that more students have opportunities for success.

Michelle Porche, Ed.D is an associate director at the Wellesley Centers for Women and senior research scientist studying academic achievement for young children and adolescents. In her investigations of achievement, the role of gender and socio-emotional factors, including childhood adversity, play a major part in her work.

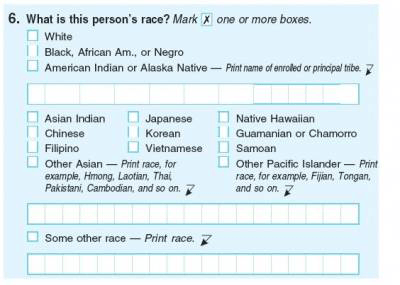

media; compelling stage models have been proposed first by Poston (1990) and then expanded by Kerwin and Ponterotto (1995). In addition, Fhagen-Smith’s (2003) WCW Working Paper also described a stage model of mixed ancestry identity development. Children grow up taking on the identity community to them by their immediate family for the most part, although

media; compelling stage models have been proposed first by Poston (1990) and then expanded by Kerwin and Ponterotto (1995). In addition, Fhagen-Smith’s (2003) WCW Working Paper also described a stage model of mixed ancestry identity development. Children grow up taking on the identity community to them by their immediate family for the most part, although