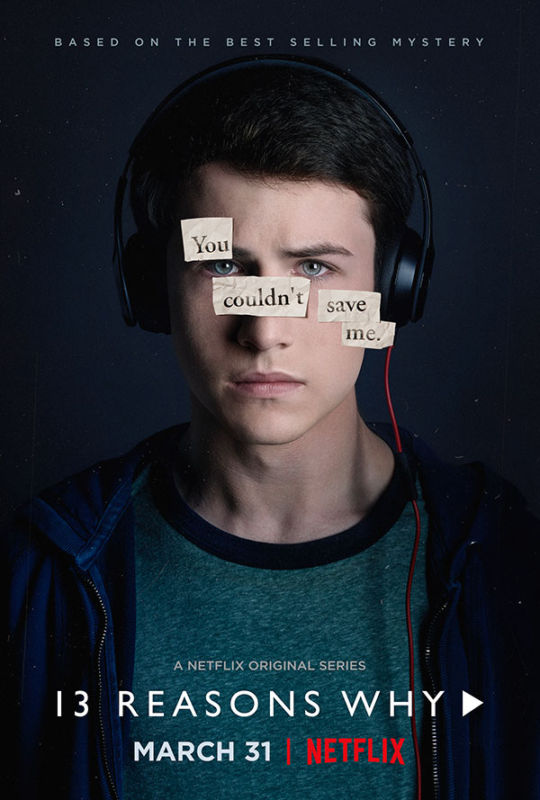

By now, parents and professionals have reacted to the new Netflix series, 13 Reasons Why. Mental health advocates and school administrators have highlighted the risks of depicting suicide as a means of revenge, of dramatizing teen suicide, and of showing school counselors as uncaring and ineffective. I would be remiss if I did not add my voice to others' by expressing my dismay that this program exposes teens to such unhealthy messages about such an important topic, and that teen depression is presented as a malady that can only be addressed through suicide.

Rather than repeating the many critiques of this series, my purpose here is to share correct messages about adolescent depression and suicide that we, as professionals and parents, should know and should be sharing with our children. Of course this is a difficult topic to broach with adolescents, but given that so many teens have watched this series already, we must embrace this opportunity to teach our children, and ourselves, about youth depression and suicide. This conversation is particularly important now, in the midst of Mental Health Awareness Month.

In fact, suicide is the third leading cause of death among adolescents, and rates of suicidal thinking and behavior are particularly high among Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual youth. While youth depression and youth suicide are distinct concerns, approximately half of all teens that die by suicide have a mood disorder, such as depression, at the time. Adolescent depression is quite common, with approximately 11 percent of all teens experiencing depression during adolescence. Although youth depression is prevalent and impairing, we now have available numerous depression prevention and treatment protocols that work. Thus, most teens who struggle with depression go on to lead healthy and productive lives.

How do we know if a teen might be experiencing depression or considering suicide? Among other symptoms, signs of youth depression include low mood or irritability, lack of interest in activities, a change to sleep or eating patterns, reduced concentration, fatigue, low self-esteem, and thoughts of death or suicide. Of course all teens experience such symptoms now and then. We worry about teens that experience a cluster of these symptoms, and when these symptoms persist over a period of at least two weeks.

Likewise, we worry about teens that exhibit signs of suicide. Sometimes these signs are subtle, such as giving away prized possessions, withdrawing from friends, or exhibiting significant behavioral changes, such as intense fights with family and friends. Teens thinking about suicide may also provide verbal cues, such as, “I wish I were dead” and “It’s not worth it anymore.” Also, many people who contemplate suicide do so because they believe they are a burden to others, and that they will be doing others a favor if they are no longer here. Thus, if you hear a teen say, “My family would be better off without me,” it is important to take action. Remember that 50-70 percent of people who make a suicide attempt communicate their intent prior to acting, mostly through such actions or verbal cues. Thus, if you recognize any of these signs, it is important to ASK. Although many of us find it scary to ask about suicide, or worry that asking about suicide will give someone the idea to attempt suicide, we know from numerous studies that talking about suicide will not lead to suicidal behavior.

Likewise, we worry about teens that exhibit signs of suicide. Sometimes these signs are subtle, such as giving away prized possessions, withdrawing from friends, or exhibiting significant behavioral changes, such as intense fights with family and friends. Teens thinking about suicide may also provide verbal cues, such as, “I wish I were dead” and “It’s not worth it anymore.” Also, many people who contemplate suicide do so because they believe they are a burden to others, and that they will be doing others a favor if they are no longer here. Thus, if you hear a teen say, “My family would be better off without me,” it is important to take action. Remember that 50-70 percent of people who make a suicide attempt communicate their intent prior to acting, mostly through such actions or verbal cues. Thus, if you recognize any of these signs, it is important to ASK. Although many of us find it scary to ask about suicide, or worry that asking about suicide will give someone the idea to attempt suicide, we know from numerous studies that talking about suicide will not lead to suicidal behavior.

How do you ask a teen if s/he might be thinking about suicide? Ask the question directly. It is okay to ask a teen if s/he has ever felt like it would be better if they were dead, or if, when very upset, they have experienced suicidal thoughts. If a teen acknowledges suicidal thoughts, s/he should be provided reassurance that help is available, and should be brought for an evaluation and treatment immediately. It’s important to remember that most people who talk about suicide do not really want to die. In fact, most suicides are not impulsive acts, and most people who contemplate suicide give many cues of their intentions, making suicide a largely preventable form of death in the United States.

The primary danger of 13 Reasons Why is that it reinforces damaging myths about youth depression and suicide. Now that this series has been released, and knowing that our teens may well have watched it, our best course of action is to counter those damaging myths by sharing important truths about teen depression and suicide.

Tracy Gladstone, Ph.D. is an associate director and senior research scientist at the Wellesley Centers for Women at Wellesley College, as well as the director of the Robert S. and Grace W. Stone Primary Prevention Initiatives, which focus on research and evaluation designed to prevent the onset of mental health concerns in children and adolescents.

References:

Avenevoli, S., Swendsen, J., He, J., Burstein, M., & Merikangas, K. R. (2015). Major depression in the national comorbidity survey–adolescent supplement: Prevalence, correlates, and treatment. Journal of The American Academy Of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 54(1), 37-44. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2014.10.010

Berkowitz, Larry (2017). Suicide Assessment and Intervention Training for Mental Health Professionals [PowerPoint slides]. NEAS, 2400 Post Road, Warwick, RI.

Burton, C. M., Marshal, M. P., Chisolm, D. J., Sucato, G. S., & Friedman, M. S. (2013). Sexual minority-related victimization as a mediator of mental health disparities in sexual minority youth: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of youth and adolescence, 42(3), 394-402.

Gould, M.S., Marrocco, F.A., Kleinman, M., Thomas, J.G., Mosstkoff, K., Cote, J., & Davies, M. (2005). Evaluating iatrogenic risk of youth suicide screening programs: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA, 293(13), 1635-43.

Joiner, T. (2009). The interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior: Current empirical status. Psychological Science Agenda, 23(6).

Kann, L., Kinchen, S., Shanklin, S. L., Flint, K. H., Hawkins, J., Harris, W. A., ... & Whittle, L. (2014). Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance--United States, 2013. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR). Surveillance Summaries. Volume 63, Number SS-4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Nadworny, E. (2016). Middle School Suicides Reach an All-Time High. www.NPR.org

Nock, M.K., Green, J.G., Hwang, I., McLaughlin, K.A., Sampson, N.A., Zaslavsky, A.M., & Kessler, R.C. (2013). Prevalence, correlates, and treatment of lifetime suicide behavior among adolescents: results from the Nation Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement. JAMA Psychiatry, 70(3), 300-10.

QPR Institute. QPR Online Gatekeeper Training for ORGANIZATIONS [Training modules]. Retrieved from https://www.qprinstitute.com/organization-training

Robins, E., Gassner, S., Kayes, J., Wilkinson Jr, R. H., & Murphy, G. E. (1959). The communication of suicidal intent: a study of 134 consecutive cases of successful (completed) suicide. American Journal of Psychiatry, 115(8), 724-733.

The JED Foundation. (2017). 13 Reasons Why: Talking Points [Leaflet]. Retrieved from https://www.jedfoundation.org/13-reasons-why-talking-points/

World Health Orgranization. (2004, September 8). Suicide huge but preventable public health problem, says WHO [Online forum post]. Retrieved from WHO Media centre website: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2004/pr61/en/

When you subscribe to the blog, we will send you an e-mail when there are new updates on the site so you wouldn't miss them.

Comments 1

I was encouraged to read about this powerful, creative response by some Michigan high school students: "13 Reasons Why Not." https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/inspired-life/wp/2017/05/09/13-reasons-why-not-students-share-personal-struggles-with-whole-school-in-effort-to-prevent-suicide/?utm_term=.b2a874a4ea3c

The story notes, citing the Centers for Disease Control, that "suicide rates among women have increased among every age cohort except those older than 75 since 1999, with the largest increase being among girls ages 10 to 14."