In 2018, I began a multi-year clinical trial to compare the effectiveness of two approaches to preventing depression in teens. One of the approaches is an online intervention -- an app -- called CATCH-IT and the other is an in-person group therapy intervention.

In 2018, I began a multi-year clinical trial to compare the effectiveness of two approaches to preventing depression in teens. One of the approaches is an online intervention -- an app -- called CATCH-IT and the other is an in-person group therapy intervention.

When we started recruiting teens to participate in the trial just this past winter, we encountered a number of challenges. It was difficult to get teens and their parents to commit to attending the weekly group therapy sessions, and to fill out the assessments we needed for our evaluation. Because we planned to hold these sessions at the clinics where our participants received their primary care, geography determined who could participate. We were busy working through these challenges throughout the early spring.

Then the pandemic hit, and with it we noticed a spike in the number of teens we were encountering who were reporting significant struggles with depression and suicidal thinking. At this point it’s too early to determine whether or not the stress of COVID accounts for the symptoms we are identifying, but regardless, we have been busy referring teens to therapists in their communities, rather than enrolling them in our study. Clearly these teens need more than we can offer in a prevention trial. We are grateful that we have been able to identify so many teens who are in need of immediate support, and to facilitate their connection to those who can offer them the help they need.

For teens with milder symptoms who are at risk of depression, and who are therefore good candidates for our study, we’ve had to reassess the way we had originally planned to conduct our research. The challenges of COVID have tied many researchers’ hands -- not being able to see people in person can prevent a lot of research from happening at all. But for us, despite the challenges presented by COVID, we have also recognized that the pandemic has allowed us to make our interventions more accessible, and has enabled us to more easily reach participants for enrollments and assessments.

The main change we had to make in our research strategy was to switch our in-person group therapy model to live online sessions. Fortunately, research shows that telehealth is just as effective as in-person therapy, even for groups, and the pandemic has made telehealth much more widely accepted and available. For our purposes, moving our in-person groups to an online format improves our study design by making the two programs we are comparing much more similar: instead of comparing the CATCH-IT app to in-person sessions, we’re now comparing two online interventions to see which is more effective and for whom.

Moving everything online has also made the group therapy much more accessible. Teens and their parents no longer need to drive to a clinic on a Sunday evening, squeezing the session in between soccer practice and homework. Since life has slowed down and schedules have eased up, teens and their families have more time, and in many cases more motivation to participate. Some teens are more comfortable interacting through a screen than sitting in a room with strangers. So far in our trial, every participant has come to every online group session, and has completed every piece of paperwork we need -- an unheard-of scenario in pre-COVID times.

In addition, we’ve been able to open up the study to more teens in more locations, and to run groups across communities. Urban, suburban, and rural teens, previously separated by geography into separate group sessions, now meet together online (very successfully, I might add). Those who live too far away to have the option of a group therapy model can now participate in it. Since we can’t be in doctors’ offices to recruit participants, we’ve changed our strategy there, too, introducing a public health campaign that reaches anyone who is interested across three states.

Although COVID has been challenging for many teens and has challenged us from a study design perspective, the current circumstances have enabled us to identify and refer many more teens with serious mental health concerns, and also have enabled more teens from different places to access our interventions. We’ll continue to follow the participants in our programs over the next 18 months and will assess how they’re doing. Even after the pandemic ends, we are planning to use what we’ve learned during this difficult time so that we’re able to make prevention interventions accessible to more people in the future. Having to adjust our methods has given us better data, and eliminated many of the barriers to mental health care for teens and their families.

Tracy Gladstone, Ph.D., is an associate director and senior research scientist at the Wellesley Centers for Women, as well as the inaugural director of the Robert S. and Grace W. Stone Primary Prevention Initiatives, which aim to research, develop, and evaluate programs to prevent the onset of depression and other mental health concerns in children and adolescents.

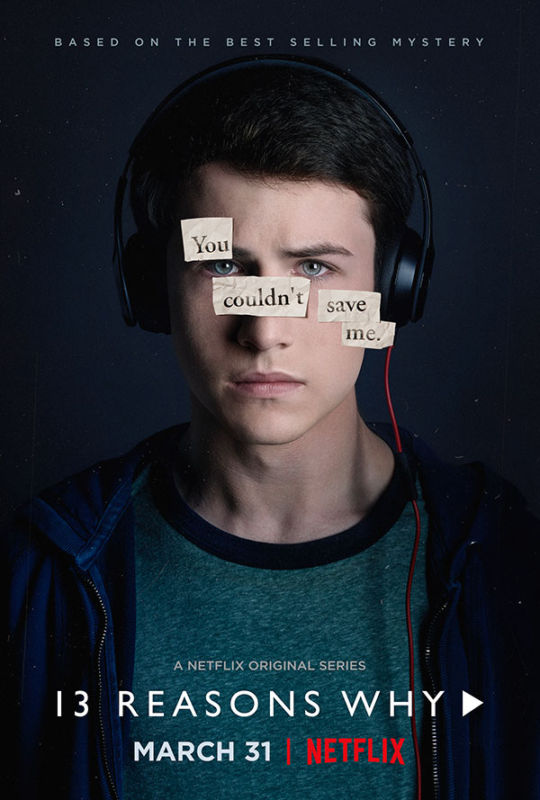

Likewise, we worry about teens that exhibit signs of suicide. Sometimes these signs are subtle, such as giving away prized possessions, withdrawing from friends, or exhibiting significant behavioral changes, such as intense fights with family and friends. Teens thinking about suicide may also provide verbal cues, such as, “I wish I were dead” and “It’s not worth it anymore.” Also, many people who contemplate suicide do so because they believe they are a burden to others, and that they will be doing others a favor if they are no longer here. Thus, if you hear a teen say, “My family would be better off without me,” it is important to take action. Remember that 50-70 percent of people who make a suicide attempt communicate their intent prior to acting, mostly through such actions or verbal cues. Thus, if you recognize any of these signs, it is important to ASK. Although many of us find it scary to ask about suicide, or worry that asking about suicide will give someone the idea to attempt suicide, we know from numerous studies that talking about suicide will not lead to suicidal behavior.

Likewise, we worry about teens that exhibit signs of suicide. Sometimes these signs are subtle, such as giving away prized possessions, withdrawing from friends, or exhibiting significant behavioral changes, such as intense fights with family and friends. Teens thinking about suicide may also provide verbal cues, such as, “I wish I were dead” and “It’s not worth it anymore.” Also, many people who contemplate suicide do so because they believe they are a burden to others, and that they will be doing others a favor if they are no longer here. Thus, if you hear a teen say, “My family would be better off without me,” it is important to take action. Remember that 50-70 percent of people who make a suicide attempt communicate their intent prior to acting, mostly through such actions or verbal cues. Thus, if you recognize any of these signs, it is important to ASK. Although many of us find it scary to ask about suicide, or worry that asking about suicide will give someone the idea to attempt suicide, we know from numerous studies that talking about suicide will not lead to suicidal behavior.