This blog was originally published on the HowlRound website on December 1, 2015, and is re-posted with permission.

This week on HowlRound, we continue the conversation on gender parity, which has been gaining momentum this year through studies, articles, forums, one-on-one discussions, and seasons and festivals focused on women. As Co-President of the Women in the Arts & Media Coalition and VP of Programming for the League of Professional Theatre Women, I have the pleasure of working with, coordinating, contributing to, and raising awareness about many of these local, national, and international efforts. This series explores what needs to happen right now—in this precipitous moment—in order to profoundly, permanently expand the theatrical community's views and visions of women, both onstage and in every aspect of production.

When people unfamiliar with the world of theatre learn that our current research is on why there are too few women leading major U.S. theatres, their first comment is, “But it’s better than it used to be, right?” We say, “No, the situation hasn’t changed for decades.” They respond with, “I don’t understand, look at Lynne Meadow, look at Diane Paulus.” We say, “Yes, there are a few illustrious examples.” Unfortunately, comparisons with the “bad-old-days” and mention of token successes also showed up frequently in our interviews with 100 theatre professionals. Furthermore, they added, “Racial minorities have it worse, that’s where we should focus our attention to diversify leadership.”

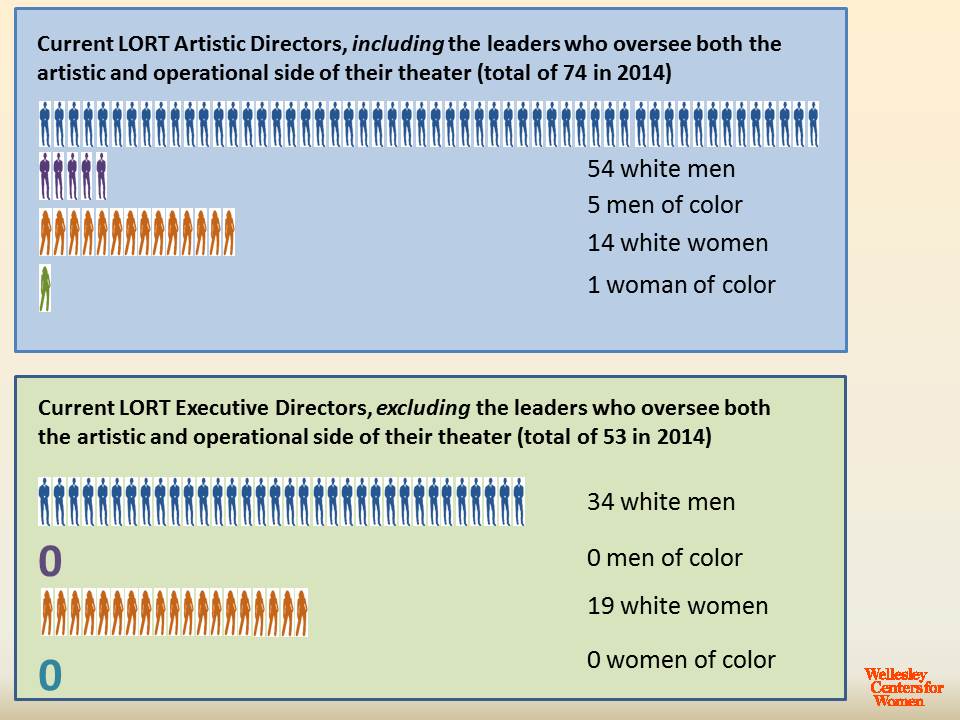

In 2013, the leadership of the American Conservatory Theater in San Francisco approached us at the Wellesley Centers for Women to be their research partner for studying gender equity in LORT leadership. There were only fifteen women who served as artistic directors, or held the combined Artistic Director/CEO position in the seventy-four LORT theatres at the time. The situation on the executive/managerial side of the theatres was better, but not much: there were nineteen female leaders. There was only one female artistic director of color. For men of color, leadership representation was also bleak: there were five leaders on the artistic side, and like women of color, none were top executive/managerial leaders. Our research, which is supported by the Virginia B. Toulmin Foundation and individual donors, suggests that many issues associated with the scarcity of women in top leadership are also true of people of color. Pointing to the scarcity of people of color to avoid paying attention to women is an excuse. There needs to be action on both fronts, paying particular attention to the virtual absence of women of color in theatre leadership.

Our research strategy aimed at better understanding the career paths of those in current leadership in order to make recommendations for aspiring future leaders in the pipeline and examining the search process to make recommendations to hiring committees. We had two informant pools: our primary charge was within LORT, so we focused on current leaders and their immediate reports within the League through interviews and resume analyses. Because candidates for leadership can come from both inside and outside of LORT, we also gathered anonymous survey data from stage director members of SDC and operational managers in TCG theatre members with a budget of over $1 million.

Demographics (of gender and race) in LORT Leadership. Photo courtesy of Wellesley Centers for Women.

First, we studied the pipeline. The career path toward an artistic director (AD) position is strongly defined by “whom you play in the sandbox with,” in the words of one of our interviewees. The skills of directing and producing can best be honed by getting invitations from multiple theatres to bring a variety of plays to the stage. But skills are not enough. To have a shot at top leadership, directors and producers need to build relationships with people who can speak to their strengths and can vet their reputation. In our survey with almost 1,000 stage directors, women highlighted two barriers toward succeeding in their quest to become the artistic leader of a theatre: a lack of opportunities to direct widely to strengthen their portfolio, and not having someone speaking to their strengths. Stage directors of color (both women and men) added to these two barriers faced by white women that they also confronted being pigeonholed into directing plays by playwrights of color.

So, yes, there is a pipeline issue facing women and people of color in their preparation for artistic leadership. How do we strengthen the pipeline?

1. Make conscious, planned, and thoughtful decisions to include women and people of color as directors and producers in programming each and every season to provide them with frequent, varied opportunities.

2. Travel and relocation are real obstacles for both men and women with families, but the preconceived notion that “they won’t want to come and do this” is a stronger barrier for women. If these issues do present a challenge, be willing to accommodate the director’s needs.

3. ADs should invite directors of color to direct the classics as well as new plays to support their portfolio growth.

A word of caution: To conclude that the main problem is a pipeline issue and over time more women and people of color will become viable candidates is an incomplete diagnosis of the problem, and an excuse. It dismisses the large numbers of producers and directors who are well prepared and eager to take on artistic director positions. In addition to the pipeline, there is just as profound a glass ceiling that can be broken with a change in mindset among those who make hiring decisions. Here are some action points for hiring committees about selecting ADs:

A word of caution: To conclude that the main problem is a pipeline issue and over time more women and people of color will become viable candidates is an incomplete diagnosis of the problem, and an excuse. It dismisses the large numbers of producers and directors who are well prepared and eager to take on artistic director positions. In addition to the pipeline, there is just as profound a glass ceiling that can be broken with a change in mindset among those who make hiring decisions. Here are some action points for hiring committees about selecting ADs:

1. Don’t overlook the sizable number of women directors and producers, including women of color, who have founded theatre companies, and have developed expertise in all aspects of artistic leadership. These women constitute a viable, immediately available pool of candidates, but are being overlooked in searches and are waiting just below the glass ceiling. Curiously, we found previous AD experience to be prevalent in the background of male, but not female artistic directors within LORT.

2. Be willing to go beyond your comfort zone and the current model of the male leader to trust and select women (and people of color) candidates. A fair number of female LORT ADs had worked in a LORT theatre prior to their AD appointment. These women were known and trusted, hence were promoted. There are many other talented women (directors and creative producers) who have the necessary skills without having worked in LORT. They need to be pulled into the search process.

3. Learn how to and then actively support any candidate’s success once on the job and continue to mentor them. One AD of color we interviewed points out that gender should hardly matter in choosing a candidate: “... nobody is prepared for one of these jobs when they come into it.” All new hires, male or female, people of color or white, will need support from their Board to succeed.

4. Move toward developing metrics for vetting leadership candidates to create greater transparency in the selection process and provide guidance to people in the pipeline. These metrics can also be used to evaluate the wisdom of the board’s selection and the performance of the candidate chosen.

Women have fared slightly better on the operational side of LORT theatres, outnumbering men in all departments, except executive/managerial directors (ED). So there is no pipeline problem for ED appointments; the absence of women at the top is clearly a glass ceiling issue. All it will take is for search committees to have the resolve to move beyond the model of having a man as the operational leader. But the lack of a pipeline issue for women aspiring to become EDs is true only for white women. Women of color are far fewer on the operational side and there is no woman of color who is the ED of a LORT theatre. For women of color, there is both a pipeline and a glass ceiling issue preventing their presence at the top. In our surveys, both women of color and white women’s comfort and expertise with fundraising come through as their strongest assets, and should be reasons for Board selection committees to seek them out. Indeed, a background in development is well represented among white female EDs. However, women managers reported that they are just as comfortable with budgeting, contracts, or real estate law. Ignoring these talents by placing the majority of women in development is limiting the pipeline and solidifying stereotypes that general management and finance are male domains.

Breaking the glass ceiling by creating more opportunities for women and people of color among current leadership in LORT now, without further delay, will serve as a route to simultaneously grow the pipeline reaching all the way down to high school teens who will learn to see the theatre as a possible and viable option among their career choices.

Sumru Erkut, Ph.D. and Ineke Ceder are members of the research team at the Wellesley Centers for Women, working on the Women's Leadership in Residential Theaters project.

Comments