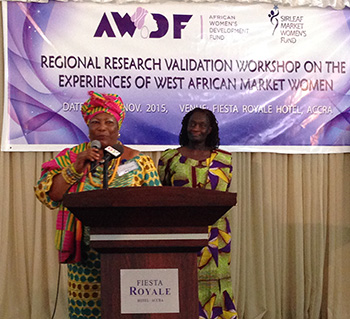

This past November, I had the opportunity to visit Ghana as a member of the international research advisory committee for a study on West African market women that was sponsored by the African Women’s Development Fund, Ford | West Africa, and the Sirleaf Market Women’s Fund (full disclosure: I’m a member of the SMWF board). This sweeping study, in which over 500 women from four Anglophone countries--Ghana, Liberia, Nigeria, and Sierra Leone--were interviewed, was the first ever to examine market women’s contributions to economic and social development in West Africa, particularly from the perspective of the market women themselves. Five researchers--a coordinating lead researcher, Dr. Comfort Lamptey, plus one researcher for each country--collected and analyzed the data, and we were convening in Ghana for a validation workshop to which national government officials, UN operatives, NGO leaders, funders, and market women leaders had been invited to discuss the results and formulate next steps.

Market women--those everyday traders who sell foodstuffs and other necessities in local open markets--are a force to be reckoned with in their respective countries. Yet, their voices, concerns, and ideas have often been ignored because they are considered economically and socially marginal due to their location in the informal sector and the fact that many continue to live at subsistence level. Nevertheless, as our study showed, market women make up approximately 80 percent of the women working in the informal sector in their societies, and, without them, their countries couldn’t function. They are the ones responsible for moving crops and livestock from farm to market and for basic processing of foods most frequently used. Whether rice or corn, yam or cassava, plantains or peppers, pineapples or papayas, sugar cane or palm oil, greens or groundnuts, goat, chicken, or fish--they are the ones who bring it to market and sell. One thing we agreed on at this conference is that no longer should these women be referred to as “petty traders,” because there is nothing petty about what they do!

In fact, our study revealed that market women play a major role in human capital development in their respective nations because, after feeding their families, their major economic expense is paying school fees for their children--and often for the children of others, such as extended family members. In our study, there were market women paying school fees for up to 13 children; an average was four or five. Often, these women also generously take care of neglected or orphaned children in their communities, even on their subsistence-level budgets. Market women are committed to education, and many have put children not only through primary sch Layli Maparyan with the Delegation from Liberia.ool, but also secondary school and university. Some can claim heads of state, government ministers, lawyers, doctors, nurses, professors, and corporate executives among those they have educated. In fact, the head of Ford | West Africa expressed that he was in part inspired to fund this study because his own mother was a market woman. Even President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf of Liberia, Africa’s first democratically elected woman head of state, after whom the Sirleaf Market Women’s Fund is named, is the grand-daughter of a market woman. Almost everyone in West Africa--or anyone from West Africa, living in the diaspora--is related or connected to a market woman.

Layli Maparyan with the Delegation from Liberia.ool, but also secondary school and university. Some can claim heads of state, government ministers, lawyers, doctors, nurses, professors, and corporate executives among those they have educated. In fact, the head of Ford | West Africa expressed that he was in part inspired to fund this study because his own mother was a market woman. Even President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf of Liberia, Africa’s first democratically elected woman head of state, after whom the Sirleaf Market Women’s Fund is named, is the grand-daughter of a market woman. Almost everyone in West Africa--or anyone from West Africa, living in the diaspora--is related or connected to a market woman.

Although our study was able to identify the fact that market women contribute significantly to the gross domestic product (GDP) of their respective nations, further detailed study of their contributions to GDP by economists would be the next logical follow-up. Such data would provide leverage for convincing governments to earmark budgetary lines for market women. Market women have many needs, from infrastructural improvements to their markets (such as better stalls, improved storage and security, and improved water and sanitation), to financial literacy and business skills training (which will enable them to better engage formal sector institutions), to basic literacy programs (our study found that most market women have only completed primary school or less), to child care and early education schemes for their children, to family leave policies and maternal care provisions that will provide flexibility and support when they are pregnant or lactating. These are the needs that were identified by the market women themselves in our study. Although some foundations, multi- or bi-laterals, and NGOs address these needs quite valiantly, they would be most comprehensively and reliably addressed if governments became involved, creating relevant policies, contributing dedicated funds, and coordinating multi-sectoral efforts so that duplication is avoided. More detailed research about the economic impact of market women could show governments that investing in market women isn’t just the right thing to do for the women themselves, but it is also a profitable economic investment for each nation respectively, particularly as many struggle to move from low-income to middle-income economic designations.

In the study and from the floor, the market women expressed the need to strengthen their national  market women organizations, with a special focus on gender parity in leadership. Although women are, by far, the largest proportion of marketers and traders, often it is the few men who are afforded positions of leadership that allow them to engage with policymakers. The market women who participated in our study would like to see women’s voices rise to the top and for women’s leadership to be recognized with top-level posts. Additionally, they indicated that the time might be right for a West Africa-wide market women’s organization that allowed market women from different countries to network, share best practices, and shape policy that affects them. Many touted the Sirleaf Market Women’s Fund as a good example of a multi-constituency organization that has raised the visibility of market women’s issues at the same time as it has brought different stakeholders together for a common cause, and they imagined this model growing from its roots in Liberia to other countries. Additionally, the pivotal roles of the African Women’s Development Fund, UN Women, and Ford, all of which have provided funding for market women’s issues and related actions, were lauded as model donors.

market women organizations, with a special focus on gender parity in leadership. Although women are, by far, the largest proportion of marketers and traders, often it is the few men who are afforded positions of leadership that allow them to engage with policymakers. The market women who participated in our study would like to see women’s voices rise to the top and for women’s leadership to be recognized with top-level posts. Additionally, they indicated that the time might be right for a West Africa-wide market women’s organization that allowed market women from different countries to network, share best practices, and shape policy that affects them. Many touted the Sirleaf Market Women’s Fund as a good example of a multi-constituency organization that has raised the visibility of market women’s issues at the same time as it has brought different stakeholders together for a common cause, and they imagined this model growing from its roots in Liberia to other countries. Additionally, the pivotal roles of the African Women’s Development Fund, UN Women, and Ford, all of which have provided funding for market women’s issues and related actions, were lauded as model donors.

One extremely interesting and exciting development from the floor was the suggestion that market women should and would like to take more responsibility for data collection about themselves. Many market women expressed “research fatigue”--an exhaustion with “outsider” researchers who “come in, collect data on us, write books about us, don’t call us back, and don’t do anything to help us.” Fortunately, the whole purpose of the validation workshop was to present the findings to the market women, determine whether they rang true with market women, and engage in conversations about the way forward with market women as equal partners at the table with other stakeholders. At the workshop, all of us discussed ways that data and research could be maximized for the benefit of market women, including how to collect data in ways that avoid duplication and how to bring market women into the process as researchers. It is market women who know best what is important to their lives and their businesses, yet the ability of researchers from different sectors (academia, government, multilaterals, NGOs, CBOs, and funders) to converse together enriches the larger effort.

Dr. Comfort Lamptey and Layli MaparyanMy own horse in this race has to do with making sure that women all over the world have equal access to good research that affects their lives. At the Wellesley Centers for Women, we have prioritized raising the banner of research in important conversations and working with women- and gender-focused research organizations around the world to increase capacity, where needed, and to partner as equals wherever possible. We have so much to learn from each other; but, more importantly, the world’s policymakers need more and better information about women’s lives that is informed by women themselves. Whether it is creating more opportunities for women to become researchers, or making sure there are enough women- and gender-focused research organization around the world, or making sure that data generated by and about women gets utilized in all the right places, or making sure that everyday people who aren’t researchers have the research literacy to interpret research findings critically, we believe that research is a human right and that access to data advances human rights. So, on this Human Rights Day, we are glad to be part of the cause!

Dr. Comfort Lamptey and Layli MaparyanMy own horse in this race has to do with making sure that women all over the world have equal access to good research that affects their lives. At the Wellesley Centers for Women, we have prioritized raising the banner of research in important conversations and working with women- and gender-focused research organizations around the world to increase capacity, where needed, and to partner as equals wherever possible. We have so much to learn from each other; but, more importantly, the world’s policymakers need more and better information about women’s lives that is informed by women themselves. Whether it is creating more opportunities for women to become researchers, or making sure there are enough women- and gender-focused research organization around the world, or making sure that data generated by and about women gets utilized in all the right places, or making sure that everyday people who aren’t researchers have the research literacy to interpret research findings critically, we believe that research is a human right and that access to data advances human rights. So, on this Human Rights Day, we are glad to be part of the cause!

Layli Maparyan, Ph.D., is the Katherine Stone Kaufmann '67 executive director of the Wellesley Centers for Women and Professor of Africana Studies at Wellesley College.

When you subscribe to the blog, we will send you an e-mail when there are new updates on the site so you wouldn't miss them.

Comments