WCW Writer-in-Residence Laura Pappano is an award-winning journalist and author who has written about K-12 and higher education for over 30 years. Her latest book is called School Moms: Parent Activism, Partisan Politics, and the Battle for Public Education. Here, she talks about the process of reporting and writing from the front lines of this battle.

Why did you want to write about this topic at this moment in time?

Why did you want to write about this topic at this moment in time?

I have covered education for decades. I have followed what happens in schools and how it affects those trying to teach and to learn. I have sat in hundreds, if not thousands, of classrooms (I still volunteer, teaching journalism to students in grades 3-8 in New Haven, CT). But the conflicts and the actions I saw unfolding, first in specific spots around the country and then more widely, were NOT about education. Rather, I saw well-funded and well-organized far-right actors using our public schools as a platform to gain political power. With 90 percent of American children attending public schools, these institutions are critical to our social, cultural, and economic future. They need to work. I felt compelled to connect the dots, offer historical context, and challenge the wild misinformation being put out there.

With 90 percent of American children attending public schools, these institutions are critical to our social, cultural, and economic future. They need to work.

Why did you choose the title School Moms? What role does gender play in the book?

There is a rich history of women asserting their identity as mothers to organize and lead. Before the 19th Amendment enshrined the vote, in some locales women could vote and be elected to school boards. Enterprising female leaders in the early 20th century used female domestic “expertise” to extend their authority, including over schools. More recently, parent-teacher associations have relied on mothers’ labor to organize fundraisers to pay for playground upgrades, school trips, and classroom supplies. These “school moms” bring serious talent to such tasks, even as that work is underestimated.

As WCW Senior Research Scientist Sari Kerr has noted, women who take time off from professional roles face a “motherhood penalty” in lower wages and slowed careers. Yet what looks like a blank space on a resume, I argue, is actually a time of skill-building; it just doesn’t get public credit. Now, we see those skills being put to work. The book title recognizes that these moms are the ones tapping their networks and building powerful organizations to counter the attacks on public schools. They are the heroes on the front lines.

How did the work of WCW’s Peggy McIntosh and SEED shape your thinking about this topic?

Peggy McIntosh’s work, and that of SEED, was so important. I’m not sure you can discuss the gag laws on teachers around discussion of race and gender without paying homage to her work, particularly her essay “White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack.” It remains a critical piece of writing and thinking. In fact, Matthew Hawn, one of the teachers in East Tennessee who I spent time with and is in the book, was fired for discussing race, including asserting the existence of white privilege. He had assigned the McIntosh essay to his 11th grade “Contemporary Issues” class.

During summer 2022, four Wellesley College students—Laila Brustin ’25, Aidan Reid ’24, Catherine Sneed ’25, and Sunny Lu ’24—helped Pappano with research, from digging up historic documents and tracking members of moms’ groups to poring over campaign finance filings for school board races.

From School Moms: Parent Activism, Partisan Politics, and the Battle for Public Education

Public schools carry the weight of our cultural differences. Even though, for more than a century, they have been nonpartisan gathering places and a center of civic life in America, they have spurred debate. Often, friction has been over disappointing test scores, funding formulas (do school systems rely too much on property taxes?), or disagreements over how math or history should be taught. In combing through old magazines, I was struck by how often we have raised alarms about our “troubled” public schools. A headline in the March 1947 issue of Ladies’ Home Journal warns, “Our Schools Are in Danger.” A story in the February 1971 issue of Parents’ Magazine could have been written at almost any time in the previous century. Titled “Schools in Trouble,” it promised a “hard-hitting analysis of the failures of public education.”

But what is happening now is not a debate over the institution’s shortcomings. Rather, this is a move by the far right to use public schools to gain political power. The campaign by extremists ignores the messy job of educating every single child, regardless of background, circumstance, or academic ability. Instead it seizes on the convenient fact that schools touch everyone. When you control schools, you control society.

But what is happening now is not a debate over the institution’s shortcomings. Rather, this is a move by the far right to use public schools to gain political power. The campaign by extremists ignores the messy job of educating every single child, regardless of background, circumstance, or academic ability. Instead it seizes on the convenient fact that schools touch everyone. When you control schools, you control society.

What I appreciated about all the people I spent time with—whether or not they are quoted in this book—was their willingness, even eagerness, to share what they were experiencing. We have crossed a line, and people who have worked in and around education can feel it. Just as I was compelled to write this book, I heard from many that they were compelled to speak up. I am grateful that they have done so.

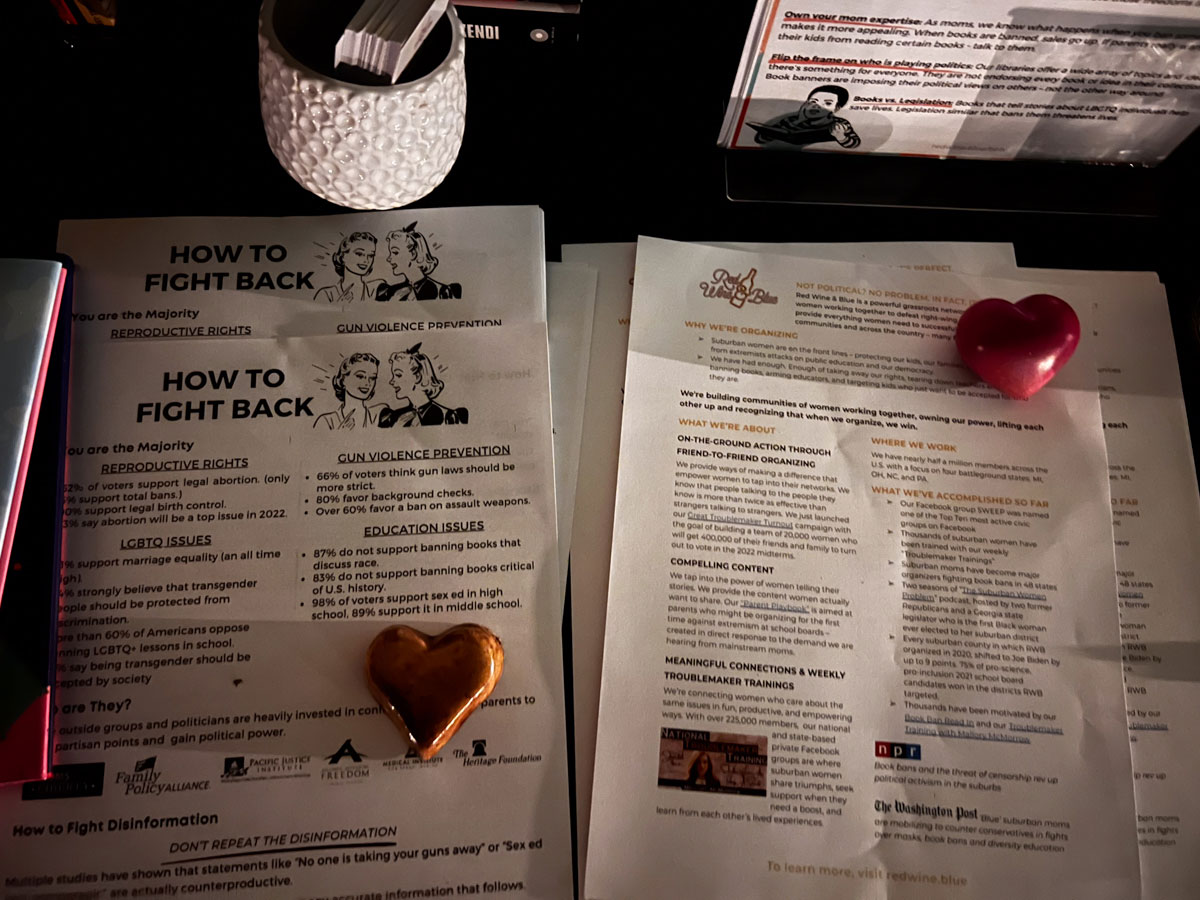

As a mother who has raised children in both suburban and urban settings and has volunteered in public schools in both, I am struck by the relentless energy and determination of today’s parents. I salute these “school moms”—a term that I intend as wholly complimentary and includes all highly active school parents—who bring serious professional skills, hours of labor, and care to the tasks they take on. They have always been around, breezing down school hallways or sitting at a checkout desk in the library to help out. But in this new environment, their tasks have shifted. Parent involvement is no longer only about organizing the back-to-school picnic and the teacher appreciation breakfast or keeping track of orders for the wrapping paper fundraiser. Now it also includes tracking school board agendas, organizing meeting turnouts, reviewing proposed state legislation, creating Facebook pages where parents first spread the word about conflict in the schools and building—and then turn those Facebook groups into bona-fide organizations with their own websites and missions. Parents have become expert in digging through campaign finance filings and other public records. They sift through news reports, connect the dots to local issues, and share. Parent involvement at this level is no longer casual. Recently a North Texas mom texted me to share an article about fallout from the book policy recently adopted by a local far-right-dominated school board requiring the district to review all book donations: the Rotary Club was rebuffed as it prepared to donate a copy of the Webster Student Dictionary to each third-grader, as it had done for over a decade. (The new edition contained twenty-two new words.)

School moms are fighting for public education in their communities. This book is about that battle—and why it matters.

School moms, in other words, are fighting for public education in their communities. This book is about that battle—and why it matters.

School moms, in other words, are fighting for public education in their communities. This book is about that battle—and why it matters.

Excerpted from School Moms: Parent Activism, Partisan Politics, and the Battle for Public Education by Laura Pappano. Copyright 2024. Excerpted with permission by Beacon Press

Laura Pappano is a writer-in-residence at WCW. A former education columnist for The Boston Globe, she has written about education for The New York Times, The Hechinger Report, The Washington Post, and others. She is the author or co-author of three other books, The Connection Gap: Why Americans Feel So Alone, Playing with the Boys: Why Separate is Not Equal in Sports, and Inside School Turnarounds.

Laura Pappano is a writer-in-residence at WCW. A former education columnist for The Boston Globe, she has written about education for The New York Times, The Hechinger Report, The Washington Post, and others. She is the author or co-author of three other books, The Connection Gap: Why Americans Feel So Alone, Playing with the Boys: Why Separate is Not Equal in Sports, and Inside School Turnarounds.