Commentary by Sari Pekkala Kerr, Ph.D.

Many studies have shown that men’s and women’s earnings diverge after they become parents: Women earn less than men in the decade or so after the birth of their first child. But what happens to women’s work, careers, and earnings when their children grow up? My colleagues Claudia Goldin, Ph.D., Claudia Olivetti, Ph.D., and I explored this in our recent paper for the National Bureau of Economic Research.

Many studies have shown that men’s and women’s earnings diverge after they become parents: Women earn less than men in the decade or so after the birth of their first child. But what happens to women’s work, careers, and earnings when their children grow up? My colleagues Claudia Goldin, Ph.D., Claudia Olivetti, Ph.D., and I explored this in our recent paper for the National Bureau of Economic Research.

As kids get older, child care demands lessen and women can take on greater career and workplace challenges. Do mothers earn more as a result of their increased work time, relative to men and to women who have not yet had, or will never have, children? To answer these questions, we examined data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979, an extraordinary sample that began in 1979 with around 13,000 14- to 22-year-old respondents. We can now look at data on these people as they advance to their mid-50s to see how their earnings have changed over time.

The Price of Being Female

We found that the story of the gender earnings gap is different for women depending on their level of education. When we compared women with college degrees to those with only high school degrees, we found that the gender earnings gap is initially larger for those with only high school degrees. In other words, men with high school degrees start out earning significantly more than women with high school degrees, whereas men and women with college degrees have less of a gap in their earnings. But by their early forties, the gender earnings gap for the two education groups switches and becomes much greater for those with a college degree. College graduate women lose out relative to their male counterparts, whereas less-educated women have earnings that remain about the same as less-educated men. This is largely a result of the very steep earnings trajectory that college-educated men encounter early in their careers.

. . . mothers’ inability to earn the same as fathers is due to the fact that having children gives men an advantage—a fatherhood premium—that women can never catch up with . . .

The Motherhood Penalty

After they become mothers, women’s hours of paid work initially plummet—more so for college graduates. College graduate mothers work fewer hours than non-mothers, but their hours increase as their youngest child begins school and eventually graduates secondary school. Among non-college graduates, on the other hand, mothers work virtually identical hours as non-mothers. Mothers increase their work time as their children grow up, but they are still behind fathers.

How do these changing work effort patterns translate to pay gaps? We were able to separate the parental gender gap into three components: the price of being female (the difference between men and women), the motherhood penalty (the difference between mothers and non-mothers), and the fatherhood premium (the difference between fathers and non-fathers). We found that the overall parental gender gap in earnings is greater for the less educated at first and then becomes greater for the more educated—similar to the story of men vs. women.

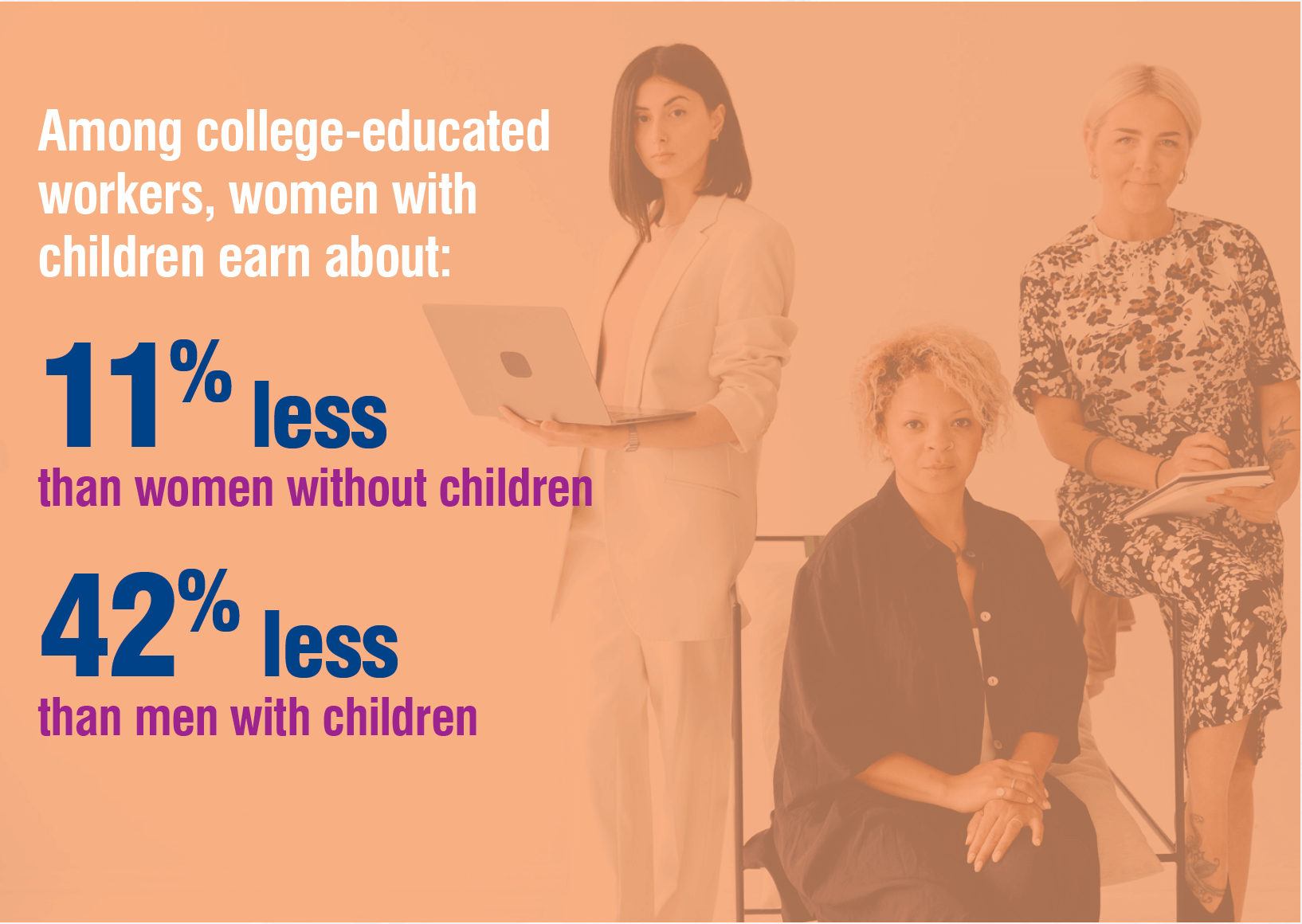

If you look at college graduate women and men ages 35-39 years old, women with children earn about 11% less than women without children. But the difference between mothers and fathers is about 42%. What accounts for the enormous difference between the parental gender gap and the motherhood penalty? It’s the fatherhood premium: the fact that not only do women earn less from their years of raising children, but men actually earn a premium when they have children.

If you look at college graduate women and men ages 35-39 years old, women with children earn about 11% less than women without children. But the difference between mothers and fathers is about 42%. What accounts for the enormous difference between the parental gender gap and the motherhood penalty? It’s the fatherhood premium: the fact that not only do women earn less from their years of raising children, but men actually earn a premium when they have children.

The Fatherhood Premium

There is a large and longstanding literature regarding the fatherhood premium. The jury is still out on whether fathers earn more because they work harder after they have children, or whether they become fathers when they are earning more, or whether supervisors reward fathers more. Whatever the reasons, among different sex couples, men are able to become fathers while continuing to advance in their careers because women disproportionately take care of the children. Mothers may cut back on their paid work hours, work less demanding jobs, and earn less. But shockingly, even women without children do worse than men with children. For men, having children and a wife who is the caregiver is related to their earnings boost. The fatherhood premium remains large and increases with age, especially among college graduates.

What can explain the persistence of the fatherhood premium? We explored the possibility that the fatherhood premium, and its increase with age, come disproportionately from fathers who have time-intensive jobs around the moment when they start their families. Men with time-intensive jobs when younger were enabled or motivated to work even harder when they had children than were men who were not fathers. Extra effort exerted when they were younger appears to have been disproportionately rewarded through career opportunities that produced higher earnings later. But mothers who began in time-intensive occupations did far worse than non-mothers in these occupations starting at age 40. One reason for these differences is that interruptions and lower hours at the start of employment are more heavily penalized in time-intensive jobs.

Over the life cycle of parenting, there is a moment when child care demands greatly lessen and mothers can increase their hours of paid work and take on more career challenges. They reach the summit and can then descend the other side of the mountain. But even though they increase their hours of work, they never enter the rich valley of gender equality. In large measure, mothers’ inability to earn the same as fathers is due to the fact that having children gives men an advantage—a fatherhood premium—that women can never catch up with, no matter how many years of work experience they have.

Sari Pekkala Kerr , Ph.D., is an economist and a senior research scientist who leads the Women in the Workplace Research Initiative at the Wellesley Centers for Women. Her studies and teaching focus on the economics of labor markets, education, and families.

, Ph.D., is an economist and a senior research scientist who leads the Women in the Workplace Research Initiative at the Wellesley Centers for Women. Her studies and teaching focus on the economics of labor markets, education, and families.